Alexia Barakou

21 March 2024 Amund Trellevik

Amund Trellevik Wojciech Cieśla

Wojciech Cieśla

Russian interference unnerves Europe as elections near

Alexia Barakou

Russian interference unnerves Europe as elections near

21 March 2024The Kremlin wants to “sow divisions” across Europe before June’s parliamentary elections using a playbook of old and new tricks.

This article is part of EU under pressure, an Investigate Europe series examining major issues ahead of European elections in June 2024.

As the 44-year-old man walked along the snow-covered pavement on his commute to the University of Tromsø, officers from Norway’s secret police approached from behind. What followed that morning in October 2022 could have come from a spy movie: a drone filming the events shows how two officers, rapidly increasing their pace, grab the man by both hands, handcuff him and lead him away.

To his colleagues he was José Assis Giammaria, a Brazilian academic specialised in Arctic security policy. In fact, he was Mikhail Mikushin, who authorities suspect was a spy for Russia’s GRU military intelligence.

Mikushin remains in detention in Oslo. He is one of several alleged Russian ‘illegals’, or deep-cover agents, identified in Europe recently. The unmasking came as Russia’s traditional intelligence network fractured - around 400 spies were expelled from European embassies following the invasion of Ukraine - and sanctions hit thousands of businesses and individuals connected to the Kremlin.

The influence of deep-cover agents might be small, but their renewed presence is indicative of a wider web of intelligence tactics now used by Vladimir Putin’s regime. And Europe is growing fearful with parliamentary elections on the horizon in June.

As the 44-year-old man walked along the snow-covered pavement on his commute to the University of Tromsø, officers from Norway’s secret police approached from behind. What followed that morning in October 2022 could have come from a spy movie: a drone filming the events shows how two officers, rapidly increasing their pace, grab the man by both hands, handcuff him and lead him away.

To his colleagues he was José Assis Giammaria, a Brazilian academic specialised in Arctic security policy. In fact, he was Mikhail Mikushin, who authorities suspect was a spy for Russia’s GRU military intelligence.

Mikushin remains in detention in Oslo. He is one of several alleged Russian ‘illegals’, or deep-cover agents, identified in Europe recently. The unmasking came as Russia’s traditional intelligence network fractured - around 400 spies were expelled from European embassies following the invasion of Ukraine - and sanctions hit thousands of businesses and individuals connected to the Kremlin.

The influence of deep-cover agents might be small, but their renewed presence is indicative of a wider web of intelligence tactics now used by Vladimir Putin’s regime. And Europe is growing fearful with parliamentary elections on the horizon in June.

Authorities suspect Mikhail Mikushin was a spy for Russia’s GRU military intelligence.

He was arrested in Tromsø, northern Norway, while working at the city's university. Credit: Shutterstock

Russia has allegedly recruited MEPs as “influence agents”, financed far-right groups, orchestrated innumerable online disinformation campaigns, as well as influencing anti-LGBT movements, academia and civil society throughout Europe.

The European Parliament warned in February that Russia was attempting to “sow divisions” across Europe. “MEPs are outraged that Russia… has found ways to provide significant funding to political parties, politicians, officials and movements in several democratic countries to interfere and gain leverage in their democratic processes.”

While Russia has targeted previous EU elections, worries about interference around the 2024 vote are particularly acute. Russia will use the “European elections as a kind of testing ground to see how their strategies and tactics will work out in elections in general,” says Anton Shekhovtsov, a Vienna-based Ukrainian political scientist who studies connections between the far-right in Europe and Russia.

“Their main target will be to undermine as much as possible political and public support for Ukraine. They will use, most likely, scare tactics… saying that people or politicians who help Ukraine are dragging societies into a war with Russia.”

The European Parliament warned in February that Russia was attempting to “sow divisions” across Europe. “MEPs are outraged that Russia… has found ways to provide significant funding to political parties, politicians, officials and movements in several democratic countries to interfere and gain leverage in their democratic processes.”

While Russia has targeted previous EU elections, worries about interference around the 2024 vote are particularly acute. Russia will use the “European elections as a kind of testing ground to see how their strategies and tactics will work out in elections in general,” says Anton Shekhovtsov, a Vienna-based Ukrainian political scientist who studies connections between the far-right in Europe and Russia.

“Their main target will be to undermine as much as possible political and public support for Ukraine. They will use, most likely, scare tactics… saying that people or politicians who help Ukraine are dragging societies into a war with Russia.”

“MEPs are outraged that Russia has found ways to provide significant funding to political parties, politicians, officials and movements”

— European Parliament

Germany, as the country most important for Ukraine's defence struggle alongside the US, is a priority target for Russia’s hybrid attacks, alongside fellow EU powers France and Italy. "They are the economic drivers of the entire EU,” Shekhovtsov says. “And in terms of politics, they are the countries with the strongest voice in the Union."

Concerns about Kremlin interference around Brussels are at fever-pitch. In January Russian investigative outlet the Insider alleged that Latvian MEP Tatjana Ždanoka had for years worked for the FSB, Russia’s security service. There are others too, say the European Parliament, which claimed several unnamed MEPs were “knowingly serving Russia’s interests”. In 2022, a former Hungarian MEP was jailed for spying on the EU for Russia.

Concerns about Kremlin interference around Brussels are at fever-pitch. In January Russian investigative outlet the Insider alleged that Latvian MEP Tatjana Ždanoka had for years worked for the FSB, Russia’s security service. There are others too, say the European Parliament, which claimed several unnamed MEPs were “knowingly serving Russia’s interests”. In 2022, a former Hungarian MEP was jailed for spying on the EU for Russia.

Latvian MEP Tatjana Ždanoka is accused of having spent years spying for Russia. European Union

Analysts warn that the elections could result in victories for MEPs who do not support aid to Ukraine or are even pro-Russian, especially in the far-right Identity and Democracy group.

Germany’s far-right AfD party, which currently has nine MEPs, believes Europe must resume cooperation with Russia to ensure peace and prosperity. Its alleged links to Moscow were burnished recently after Der Spiegel and the Insider reported that an aide to an AfD member of the German parliament had contact with an FSB colonel about receiving "financial support" for the party’s lawsuit against arms supplies to Ukraine.

If parties like AfD and the Dutch Party for Freedom (PVV), which has also faced criticism over perceived Russia links, succeed in June, they could impact debates ahead of national elections, “potentially shifting the discourse away” from support for Ukraine, the German Marshall Fund, a US think tank partly-funded by the EU, recently assessed.

Germany’s far-right AfD party, which currently has nine MEPs, believes Europe must resume cooperation with Russia to ensure peace and prosperity. Its alleged links to Moscow were burnished recently after Der Spiegel and the Insider reported that an aide to an AfD member of the German parliament had contact with an FSB colonel about receiving "financial support" for the party’s lawsuit against arms supplies to Ukraine.

If parties like AfD and the Dutch Party for Freedom (PVV), which has also faced criticism over perceived Russia links, succeed in June, they could impact debates ahead of national elections, “potentially shifting the discourse away” from support for Ukraine, the German Marshall Fund, a US think tank partly-funded by the EU, recently assessed.

The Moscow headquarters of the FSB, Russia's security service.Shutterstock

French authorities, meanwhile, are investigating Jean-Luc Schaffhauser, a former far-right MEP over allegations he led a campaign to promote Russian interests ahead of the elections. Schaffhauser has long-standing ties to Russia and reportedly organised two loans for Marine Le Pen’s National Front party, including one of €9.4 million from a Russian bank in 2014.

Another French MEP came under scrutiny in 2019 after it emerged that the daughter of Dmitry Peskov, Vladimir Putin’s spokesperson, was interning in the office of Aymeric Chauprade. An inquiry by France’s parliament last year assessed that Le Pen’s party had acted as a “communication channel” for Russia, which itself was “conducting a long-term disinformation campaign in our country”.

Despite concerns, the impact from perceived Russian influence around Brussels remains largely unknown. On 29 February MEPs voted overwhelmingly to support Ukraine with “whatever is needed for Kyiv to win its war against Russia”.

Another French MEP came under scrutiny in 2019 after it emerged that the daughter of Dmitry Peskov, Vladimir Putin’s spokesperson, was interning in the office of Aymeric Chauprade. An inquiry by France’s parliament last year assessed that Le Pen’s party had acted as a “communication channel” for Russia, which itself was “conducting a long-term disinformation campaign in our country”.

Despite concerns, the impact from perceived Russian influence around Brussels remains largely unknown. On 29 February MEPs voted overwhelmingly to support Ukraine with “whatever is needed for Kyiv to win its war against Russia”.

MEPs at the extraordinary plenary session on the situation in Ukraine days after the invasion.European Union

The spread of disinformation is a key election battleground. French researchers recently detected 193 websites spreading false claims promoting Russia's invasion of Ukraine and criticising the West. A major pro-Russian disinformation campaign was also unearthed in Germany in January. An analysis found that around one million tweets were sent from 50,000 fake accounts over a four-week period criticising the government and its support for Ukraine.

In the year after the invasion, Russian disinformation about the EU and its allies reached at least 165 million people on social media platforms, according to a report on the EU Digital Services Act. This increased further in the first half of 2023, following the lifting of Twitter's security standards. Meta says it has set up dedicated teams in Europe to combat disinformation on Facebook and Instagram around the elections.

In the year after the invasion, Russian disinformation about the EU and its allies reached at least 165 million people on social media platforms, according to a report on the EU Digital Services Act. This increased further in the first half of 2023, following the lifting of Twitter's security standards. Meta says it has set up dedicated teams in Europe to combat disinformation on Facebook and Instagram around the elections.

“It's not a bomb that can kill you, but a poison that can colonise your minds.”

— Josep Borrell

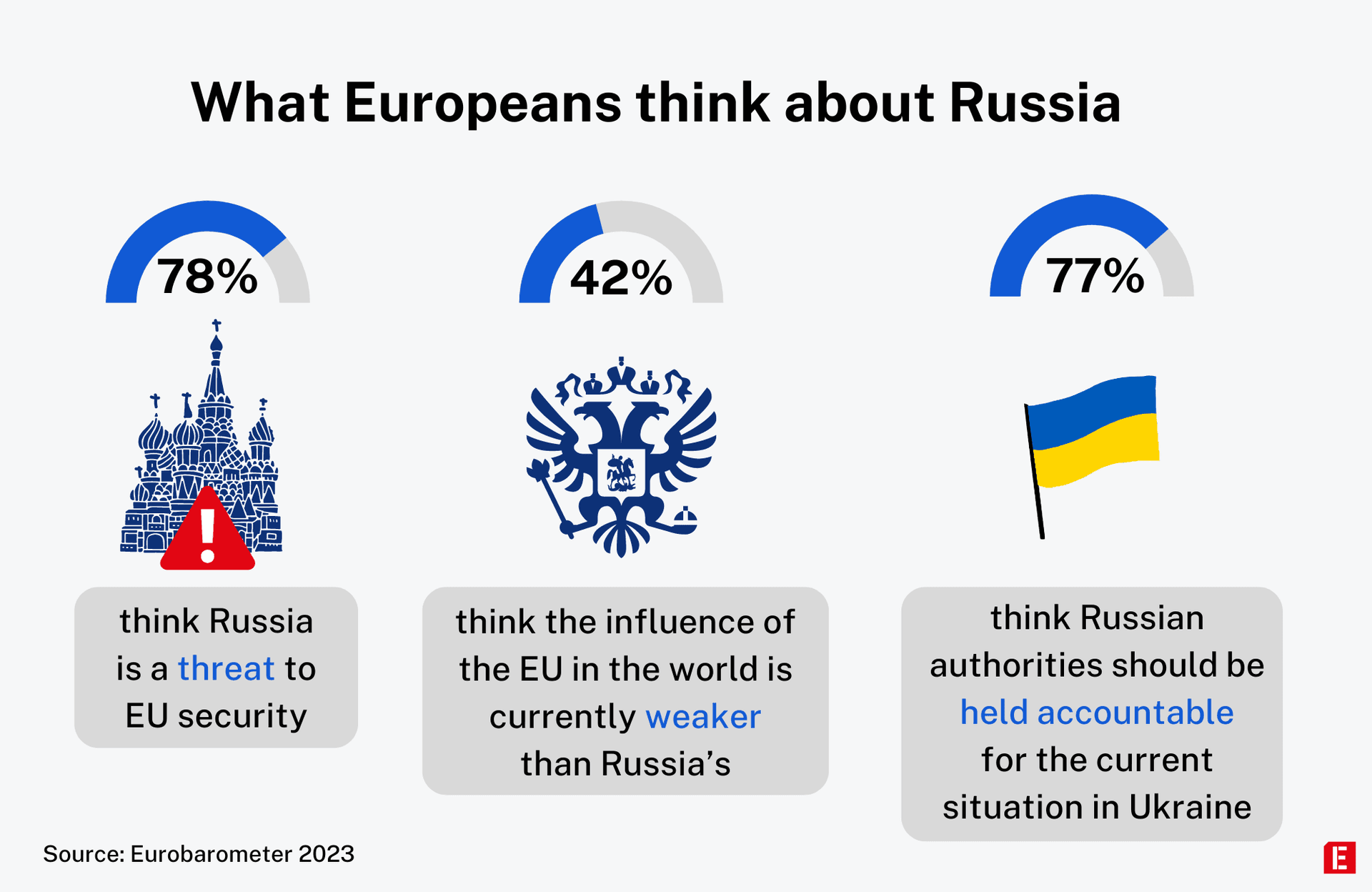

A Eurobarometer poll last December found that 78 per cent of Europeans perceive Russia as a threat to EU security. The EU’s top diplomat Josep Borrell raised the alarm in January about interference online: “It's not a bomb that can kill you, but a poison that can colonise your minds.”

“We cannot afford to allow foreign malicious actors to manipulate the opinions of our citizens and sow the seeds of division and hatred at the heart of our democracies,” Margaritis Schinas, a European Commission Vice President, said at the Munich Security Forum in February.

“We cannot afford to allow foreign malicious actors to manipulate the opinions of our citizens and sow the seeds of division and hatred at the heart of our democracies,” Margaritis Schinas, a European Commission Vice President, said at the Munich Security Forum in February.

Marta Portocarrero

Opinions are not only being manipulated in political circles. In Italy, where prime minister Giorgia Meloni has a staunchly pro-Ukraine stance, Russian influence is seen in subtler forms. There now exists a network of “Russian-Italian friendship” associations, according to a recent Financial Times investigation, which advance Russia’s political narratives at a local level.

Matteo Salvini, meanwhile, leader of the nationalist League party and now infrastructure minister in the Meloni government, is a well-known Putin admirer. The League party renewed a five-year agreement with Putin’s United Russia party in 2022 to facilitate “the expansion and deepening of multilateral cooperation and collaboration” between the two countries, according to Italian media.

Matteo Salvini, meanwhile, leader of the nationalist League party and now infrastructure minister in the Meloni government, is a well-known Putin admirer. The League party renewed a five-year agreement with Putin’s United Russia party in 2022 to facilitate “the expansion and deepening of multilateral cooperation and collaboration” between the two countries, according to Italian media.

Matteo Salvini, leader of Italy's League party, pictured wearing a Vladimir Putin t-shirt on a 2014 visit to Moscow.

Russian money is also pushing ultra-conservative agendas. HazteOir, a radical catholic organisation in Spain, and its advocacy group CitizenGo, known for their anti-LGBT and anti-feminist views, have reportedly received support from oligarchs close to the Kremlin.

In Portugal, there is no concrete evidence of organised influence on public institutions or political parties. Although the Russkiy Mir Foundation, which ostensibly promotes Russian culture globally via a network of institutions, has built a strong presence in the country. The state-run foundation, criticised by the EU for advancing “pro-Kremlin and anti-Ukrainian propaganda”, has for several years ran study centres at three Portuguese universities, and worked with various NGOs. However, following public pressure, the universities cut ties with the foundation last year.

Examples of alleged Russian influence can be found in various guises across Europe. A striking case emerged in Poland in the days after the Ukraine invasion.

In Portugal, there is no concrete evidence of organised influence on public institutions or political parties. Although the Russkiy Mir Foundation, which ostensibly promotes Russian culture globally via a network of institutions, has built a strong presence in the country. The state-run foundation, criticised by the EU for advancing “pro-Kremlin and anti-Ukrainian propaganda”, has for several years ran study centres at three Portuguese universities, and worked with various NGOs. However, following public pressure, the universities cut ties with the foundation last year.

Examples of alleged Russian influence can be found in various guises across Europe. A striking case emerged in Poland in the days after the Ukraine invasion.

Public criticism following the Ukraine invasion led to Portuguese universities cutting ties with the Russkiy Mir Foundation.Shutterstock

On 28 February 2022 in the town of Przemyśl, near the Ukrainian border, authorities arrested Pablo González, a reporter for the Spanish newspaper Publico. González is believed to be another agent sent to Europe by GRU to, among other things, spy on Zhanna Nemtsova, the daughter of murdered Russian opposition leader Boris Nemtsov.

Nemtsova, co-founder of the Nemtsov Foundation, and González became friends and the foundation invited him to its events, according to Agentstvo, an independent Russian media outlet. Authorities claim that when they accessed his devices, they found messages describing the contacts he had made, estimates of his expenses and information sent to the GRU. "I think I managed to sow the seeds of doubt among Euro-Atlanticists," he allegedly wrote to GRU about one conference he attended. Polish authorities declined to comment.

The case of González, who holds Russian and Spanish passports via his parents, is highly controversial. He has been held in pre-trial detention for two years and Reporters Without Borders and other rights groups are actively campaigning for his release. The Spanish government in February urged its Polish counterparts to show “once and for all” what evidence they had to prove his alleged espionage. Sources in the Polish government maintain that the evidence against González is strong.

Nemtsova, co-founder of the Nemtsov Foundation, and González became friends and the foundation invited him to its events, according to Agentstvo, an independent Russian media outlet. Authorities claim that when they accessed his devices, they found messages describing the contacts he had made, estimates of his expenses and information sent to the GRU. "I think I managed to sow the seeds of doubt among Euro-Atlanticists," he allegedly wrote to GRU about one conference he attended. Polish authorities declined to comment.

The case of González, who holds Russian and Spanish passports via his parents, is highly controversial. He has been held in pre-trial detention for two years and Reporters Without Borders and other rights groups are actively campaigning for his release. The Spanish government in February urged its Polish counterparts to show “once and for all” what evidence they had to prove his alleged espionage. Sources in the Polish government maintain that the evidence against González is strong.

Pablo González, a Spanish freelance journalist, is accused of being a GRU agent.

At least 35 European citizens have been prosecuted since the Ukraine invasion for acting on Russia’s behalf, according to a report by the Norwegian Police Security Service. They have variously obtained information about defence capabilities and critical infrastructure as well as allied activities. It is unclear what impact, if any, these activities could have on the upcoming elections.

The police chief responsible for the arrest of Mikhail Mikushin on the streets of Tromsø is clear about one thing though: Russia is taking greater risks in its intelligence operations in Europe.

“The need for intelligence on technology and knowledge in the West is now in such high demand that an agent may be sent without the necessary training,” says Gunnar Fugelsø, head of the domestic intelligence agency (PST) in Troms. Are there more such illegals in Norway? “We can't rule that out.”

Editor: Chris Matthews

The police chief responsible for the arrest of Mikhail Mikushin on the streets of Tromsø is clear about one thing though: Russia is taking greater risks in its intelligence operations in Europe.

“The need for intelligence on technology and knowledge in the West is now in such high demand that an agent may be sent without the necessary training,” says Gunnar Fugelsø, head of the domestic intelligence agency (PST) in Troms. Are there more such illegals in Norway? “We can't rule that out.”

Editor: Chris Matthews