Investment scammers slip through cracks in EU Big Tech law

Credit: Georgina Choleva/Spoovio

Thousands of Europeans are falling prey to online investment scams peddled on social media. Tech firms and public authorities are failing to shield citizens in the shadow of the Digital Services Act, Investigate Europe can reveal.

Boris Pistorius stares directly into the camera. Germany’s defence minister is addressing the nation, speaking of “rapid change, new jobs and advanced technologies” that will place Germany at the forefront of the global economy. At the end of the clip Pistorius tells Facebook viewers that this new government programme will “secure profits” for every citizen.

Fine Gael politician and current candidate for president of Ireland, Heather Humphreys, features in a news story in a popular post on Facebook: “I am delighted to introduce Quantum AI, a platform for Irish families to achieve financial independence,” she says from a podium. “The platform allows you to start with a minimum investment of just €300, and within 24 hours you can start receiving payments of up to €4,500 per week.” Humphreys assures people that the Irish government, along with its financial institutions, has now “made this process accessible and secure.”

Except Humphreys, and Pistorious, never said any of this. The videos are a part of a growing wave of elaborate AI-generated fakes created with advancing voice-cloning software and duplicated over and over as paid-for financial advertisements across social media platforms, including Facebook, TikTok and Instagram. Behind such clips lies a booming business built on deception: investment scams that use increasingly sophisticated deepfakes, doctored news articles and fabricated testimonials to conjure the illusion of official schemes or celebrity endorsements.

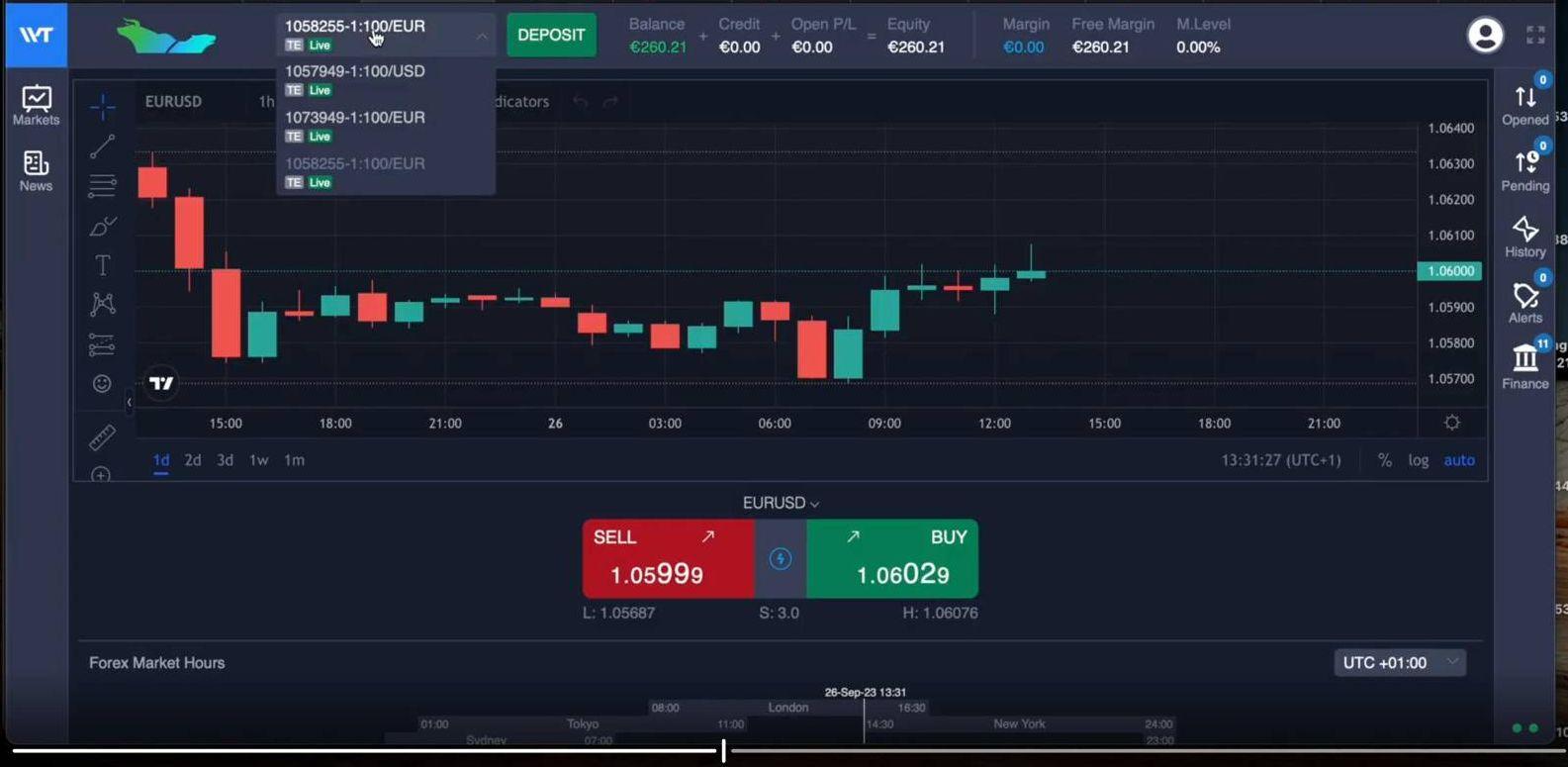

The type of investment scam promoted by these celebrity deepfakes has been proven a winner, as countless victims across Europe can attest. If a viewer likes what they see in an ad and clicks through the link, they are instructed to enter their details. With the person’s name and number now on a database, a “financial advisor” soon reaches out, asking for an initial deposit, for example, of €250. Once users turn into committed investors, this is when the hard sell begins: agents pursue targets for weeks, months even years, expertly trained to coax customers into big money investors. Victims are shown screens of fake trading platforms displaying initial profits. This emboldens them to double or even triple their initial investments. They only realise something is awry when they come to withdraw their supposed earnings. Suddenly, transfers stall and agents cannot be reached. By this point, losses may range from the hundreds of euros to in some cases over a million.

This opportunistic scam has been on the rise globally, with political leaders and prominent figures throwing their weight behind speculative cryptocurrency and lending legitimacy to such investments.

Fine Gael politician and current candidate for president of Ireland, Heather Humphreys, features in a news story in a popular post on Facebook: “I am delighted to introduce Quantum AI, a platform for Irish families to achieve financial independence,” she says from a podium. “The platform allows you to start with a minimum investment of just €300, and within 24 hours you can start receiving payments of up to €4,500 per week.” Humphreys assures people that the Irish government, along with its financial institutions, has now “made this process accessible and secure.”

Except Humphreys, and Pistorious, never said any of this. The videos are a part of a growing wave of elaborate AI-generated fakes created with advancing voice-cloning software and duplicated over and over as paid-for financial advertisements across social media platforms, including Facebook, TikTok and Instagram. Behind such clips lies a booming business built on deception: investment scams that use increasingly sophisticated deepfakes, doctored news articles and fabricated testimonials to conjure the illusion of official schemes or celebrity endorsements.

The type of investment scam promoted by these celebrity deepfakes has been proven a winner, as countless victims across Europe can attest. If a viewer likes what they see in an ad and clicks through the link, they are instructed to enter their details. With the person’s name and number now on a database, a “financial advisor” soon reaches out, asking for an initial deposit, for example, of €250. Once users turn into committed investors, this is when the hard sell begins: agents pursue targets for weeks, months even years, expertly trained to coax customers into big money investors. Victims are shown screens of fake trading platforms displaying initial profits. This emboldens them to double or even triple their initial investments. They only realise something is awry when they come to withdraw their supposed earnings. Suddenly, transfers stall and agents cannot be reached. By this point, losses may range from the hundreds of euros to in some cases over a million.

This opportunistic scam has been on the rise globally, with political leaders and prominent figures throwing their weight behind speculative cryptocurrency and lending legitimacy to such investments.

An AI-generated scam advert featuring Elon Musk shared widely on social media.

European investigators, law enforcement agencies and cybercrime experts have become increasingly alarmed by the scope and sophistication of online investment fraud flooding users’ social media feeds. This September the EU’s tech chief, Henna Virkkunen, reported that Europeans lose over €4 billion a year in online financial scam ads.

Over the last six months, Investigate Europe has uncovered how online investment fraud schemes, fuelled by suspected illegal call centres and supercharged by AI, have taken hold in Europe.

Analysis of private emails and text communication between scammers and their targets, along with interviews with dozens of victims, has revealed the extent in which Europeans are being duped into deceptive investment schemes rife across social media. Reporters conducted over 100 interviews with prosecutors, content moderators, EU officials, cybercrime specialists and bank employees, revealing how Europe is failing to protect citizens from the risk of financial ruin.

Over the last six months, Investigate Europe has uncovered how online investment fraud schemes, fuelled by suspected illegal call centres and supercharged by AI, have taken hold in Europe.

Analysis of private emails and text communication between scammers and their targets, along with interviews with dozens of victims, has revealed the extent in which Europeans are being duped into deceptive investment schemes rife across social media. Reporters conducted over 100 interviews with prosecutors, content moderators, EU officials, cybercrime specialists and bank employees, revealing how Europe is failing to protect citizens from the risk of financial ruin.

.jpg&w=3840&q=75)

German defence minister Boris Pistorius has also been used to front deepfake scam adverts on platforms.

On the hunt for scams

Valentine Auer knows the scam playbook inside out. The tech researcher leads an online fraud team at the Vienna Institute for Applied Telecommunications, appointed as a ‘trusted flagger’, for Austria. Conceived by the European Commission, trusted flaggers officially started work in 2024 as a way to boost online safety in line with the Digital Services Act (DSA), the European Union’s landmark law on published online content introduced two years earlier.Together with three colleagues, Auer hunts down specific content on large platforms and search engines such as Facebook, Instagram and Google, tracking and requesting removals to the platforms of harmful and illegal ads - including posts or ads such as investment scams, child sexual abuse material and hate speech.

Searching through the Meta ad library - a repository of paid-for ads running across all Meta-owned platforms including Instagram and Facebook - with Auer reveals the massive scale of the problem. With just a few dozen search terms, she and her colleagues pull up an avalanche of fake financial ads, many virtually identical, some tweaked slightly to evade automated filters. “We see the same tricks again and again: videos advertised for only a few hours, celebrity accounts hacked and misused for ads,” she says. “In a short time we have found tens of thousands of ads featuring well-known figures, among them the Boris Pistorius video, clearly AI-generated.”

Auer’s searches show how easy it is to find these ads, but not how difficult it is to get Meta platforms to take them down. “If we flag just a handful of ads, they’re often taken down [by the platform] within days,” she says. “But if we submit larger batches, Meta suddenly stops responding or claims the material isn't available at this time, even though we know that the content is still online.” Auer, like all ‘trusted flaggers’ across the EU, are only allowed to report 20 URLs per report at a time to Meta platforms. Given the amount of suspect ads that are flooding the platforms daily, Auer’s content monitoring work is labour intensive and time-consuming.

Credit: Georgina Choleva/Spoovio

Trusted flaggers include financial institutions, NGOs, or private companies which are selected by national authorities for expertise in a given field, such as fraud, child safety, hate speech or cyber violence. The role is not remunerated by authorities or platforms, but flaggers are given “priority” status to communicate to the tech companies through dedicated channels and individualised reports. They are independent from internal moderators hired by the large platforms to screen for harmful content, as well as third-party contractors.

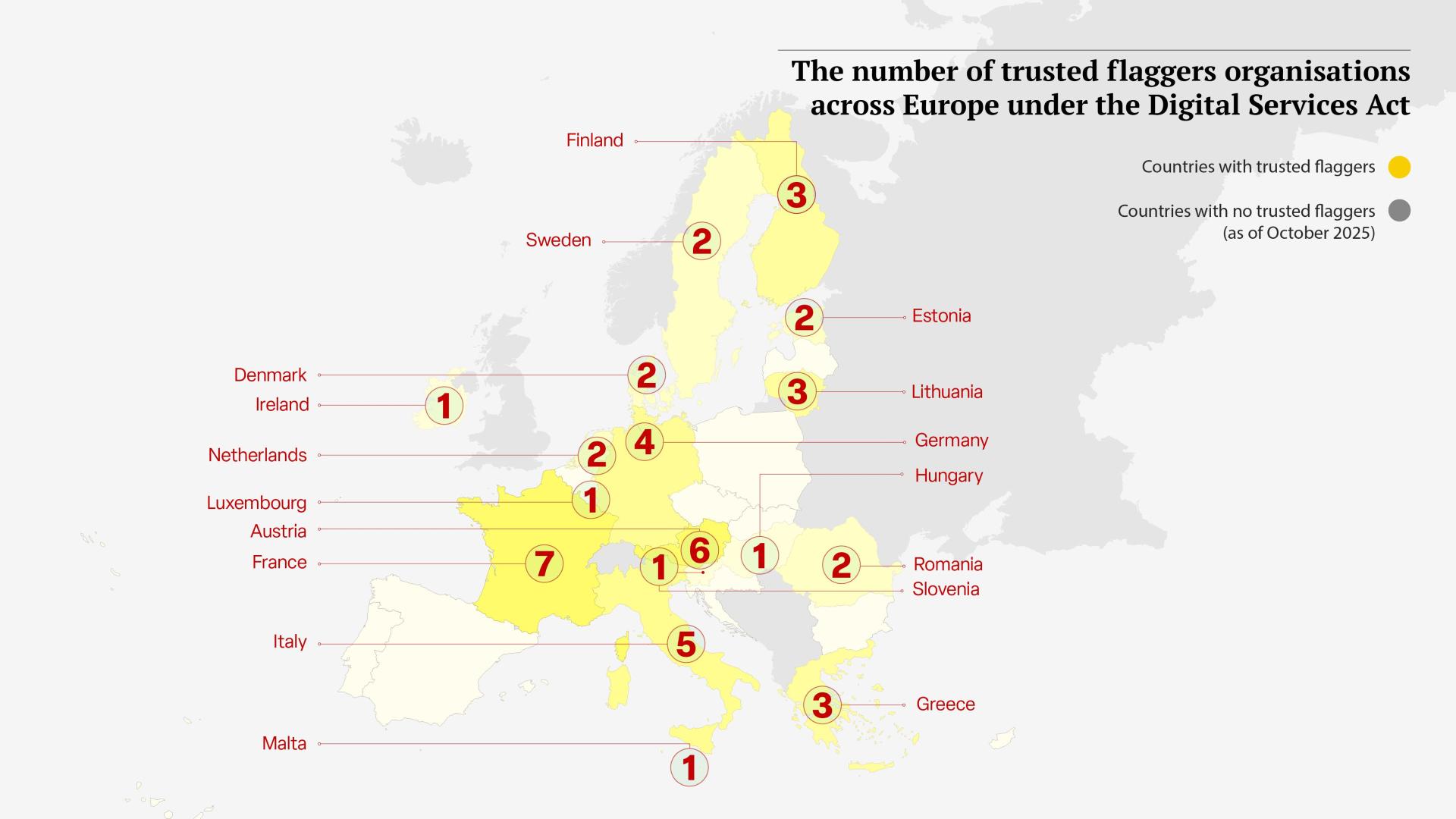

Monitoring the vast swathe of content hundreds of millions of European internet users are exposed to daily, the newly appointed trusted flaggers face an uphill battle. Currently there are just 46 trusted flagger organisations active across 17 EU member states, according to Investigate Europe’s analysis, with each focusing on their own specialist areas. More than a third of EU states have no designated flagger organisation currently in operation.

Despite best efforts by watchdogs like Auer, many national authorities and experts say large tech companies and the European Commission are struggling to rein in a rapidly evolving criminal threat.

Monitoring the vast swathe of content hundreds of millions of European internet users are exposed to daily, the newly appointed trusted flaggers face an uphill battle. Currently there are just 46 trusted flagger organisations active across 17 EU member states, according to Investigate Europe’s analysis, with each focusing on their own specialist areas. More than a third of EU states have no designated flagger organisation currently in operation.

Despite best efforts by watchdogs like Auer, many national authorities and experts say large tech companies and the European Commission are struggling to rein in a rapidly evolving criminal threat.

“Organised crime groups that used to be involved in drugs, weapons and human trafficking are increasingly turning to economic crime.”

— Sebastian Takle, Norwegian bank DNB

Online scams reach ‘unprecedented magnitude’

The European Commission has recently called financial scams in Europe a “systemic risk” to consumer protection. In 2024 it opened a formal investigation into Meta for deceptive advertising, and in the past month requested other tech titans like Apple, Google and Microsoft demonstrate their compliance with “Know Your Business Customer” rules on their apps, which they say helps to “identify suspicious entities before they cause harm”. This March, Europol’s report on organised crime warned that online financial scams, “driven by advancements in automation and AI, have reached an unprecedented magnitude, and are projected to continue growing.” In response, police forces have launched large-scale operations in Finland, Germany, Belgium, Latvia, Cyprus and the UK, dismantling networks running sprawling, sophisticated scams, targeting people in Europe and globally.Authorities in Norway and Germany say losses from financial scams now outpace other cross-border crimes. "Organised crime groups that used to be involved in drugs, weapons and human trafficking are increasingly turning to economic crime,” says Sebastian Takle, head of the Finance Cyber Crime Centre at Norway’s biggest bank DNB.

In Ireland, the national cybercrime bureau estimates digital finance fraud has stolen nearly €360 million from its citizens since 2021, with €100 million accounting for investment fraud online. In Italy, more than a quarter of its scams reported last year involved fake online trading, totaling an estimated €145 million. Investment fraud is also on the rise in Portugal. Between 2022 and 2024, police opened 3,000 enquiries into scams with crypto assets, a senior police figure told national broadcaster Renascença last year.

In Portugal, João, 57, logged onto Facebook and found an advert of what looked like Cristiano Ronaldo promoting a platform where a deposit of €250 would yield €4,000 in just one month. After weeks of reassuring phone calls from ‘financial advisors’, he discovered that his entire investment was irretrievable.

In Italy, Paolo, a retired banker, lost €15,000 after clicking on a Facebook ad about bitcoin. An apparent initial profit convinced him to pay more money for “taxes and commissions” before the operators disappeared.

In Ireland, Vlad, an IT engineer based in Dublin, clicked on an AI-generated ad featuring Elon Musk on Facebook. Over the course of several months, he was shown false identity documents from an advisor claiming financial trading credentials. Over fake investment software he thought he had earned €16,000, but couldn’t retrieve it. Today, he is still being contacted by the same agents posing as different brokers, who promise to retrieve the €6,000 they say is on the blockchain.

In Germany, a consumer protection organisation agency shared a citizen’s story who invested a reported €170,000 with USDT, a cryptocurrency via an allegedly fraudulent trading platform. They were told by an agency that “as soon as they pay 10 per cent capital gains tax, they will get all the money back.” They say they have been ruined financially from the alleged scam.

A screenshot of a fake investment platform, shared by a victim in Ireland.Credit: private individual

Uphill struggle for content watchdogs

Given Meta’s global reach and the ease of setting up advertisements, Facebook and Instagram have become a popular choice for people looking to exploit users. With some 250 million monthly users, more than half the EU’s population is on at least one Meta platform. Its worldwide advertising revenue reached $160 billion last year, accounting for 98 per cent of its global revenue. This year Meta has publicly announced how its personalised ads have provided a €213 billion boost to the European economy with business and jobs.At the same time, Meta is frequently cited as a host for scam investment products and fraudulent financial advice. The company’s advertising policy explicitly bans content that misrepresents people or organisations, as well as “misleading or deceptive claims” about financial products, but Valentine Auer says ads found by her team repeatedly violate these standards. Some ads do not show up on Meta’s ad library, but deceptive sponsored content still repeatedly appears on users’ feeds, the researcher says. They often feature deepfake celebrity and politician endorsements, according to Auer, which are also banned under Meta rules.

Sponsored ad posts on the Meta ad library also do not always provide clear information on who is actually posting and paying for the ad, despite a number of DSA requirements to do so, according to multiple trusted flaggers. “It is actually mandatory to state who paid for it [the ad], but it is usually a meaningless name,” Auer says.

It is also easy for advertisers to evade automated detection systems, says Paul O’Brien, Head of Financial Crime Intelligence at the Bank of Ireland.“You will click on an ad for an Irish tourist trip through Connemara, and really, it will be a financial scam ad.” Filtering out these ads is a full-time job, and once someone clicks on a scam ad, the algorithm continues to relentlessly feed you the same type of content across its platforms.

Compared to the rapid ascent of financial fraud across Europe, the rollout of trusted flaggers has been both slow and piecemeal. Among the 46 trusted flagger organisations officially in place across the EU, only roughly a third list scams and fraud as an area they monitor.

“There are often several versions of the same advertisement, and the fraudulent one is hidden somewhere in the middle.”

— Valentine Auer, Vienna Institute for Applied Telecommunications

Debunk EU has been a trusted flagger in Lithuania since May this year. Over a video call Viktoras Daukšas demonstrates the software his team uses to map suspected scam networks on Facebook. “We are nowadays seeing a lot of ads using deepfake and AI-generated content,” he explains. By the end of September, the small organisation had reported more than a million suspected investment fraud advertisements, which had been viewed by users around 1.4 billion times. He estimates that those who placed the ads could have paid up to €20 million for the advertising space. Like his Austrian counterpart Auer, he says he is only limited to 20 URLs per report.

National cybercrime experts share these concerns. In Poland, CERT Polska - the national Computer Emergency Response Team - has long warned that only large tech companies such as Google and Meta can truly curb the reach of online fraudsters. But, the team observed, “even though reporting mechanisms for harmful ads exist, in practice platforms process reports with significant delays or reject them, especially when the report comes from a regular user. Accounts spreading malicious ads are rarely blocked, allowing fraudsters to continue exploiting them without interruption."

Founder Thanos Sitistas says he discovered a deepfake video in early October on Facebook featuring a British investor who appeared to promote a supposed investment. By that time, the video had already been viewed by 12.3 million users, he says. Sitistas reported the video to Meta and they removed it right away, he says. But that is not always the case. Sometimes, it takes “up to a month” for Meta to decide on reported content, he adds.

Daukšas, of Debunk EU in Lithuania, agrees that Meta's response times vary greatly, claiming it can take months before the platform checks and removes content, though they say eventually most of the content gets removed.

Claudio Tamburrino works at Barzanò & Zanardo, a private consultancy and trusted flagger in Italy focusing on trademark fraud. While they don’t specifically focus on investment scams, he says that reporting content works effectively on platforms such as Temu and TikTok, whereas Meta ones often take much longer. According to Tamburrino, Barzanò & Zanardo, along with other trusted flaggers interviewed for this piece, believe that Meta’s reporting mechanism is largely managed by chatbots, and that only repeated removal requests are eventually handled by the company’s human moderators. However, most content they flag is eventually removed, he says.

National cybercrime experts share these concerns. In Poland, CERT Polska - the national Computer Emergency Response Team - has long warned that only large tech companies such as Google and Meta can truly curb the reach of online fraudsters. But, the team observed, “even though reporting mechanisms for harmful ads exist, in practice platforms process reports with significant delays or reject them, especially when the report comes from a regular user. Accounts spreading malicious ads are rarely blocked, allowing fraudsters to continue exploiting them without interruption."

Erratic response times from Meta

Once suspect content is identified, flaggers say it can take days or weeks to be removed. Greece Fact Check has been working as a certified trusted flagger for almost a year, and covers scams and frauds in its mandate.Founder Thanos Sitistas says he discovered a deepfake video in early October on Facebook featuring a British investor who appeared to promote a supposed investment. By that time, the video had already been viewed by 12.3 million users, he says. Sitistas reported the video to Meta and they removed it right away, he says. But that is not always the case. Sometimes, it takes “up to a month” for Meta to decide on reported content, he adds.

Daukšas, of Debunk EU in Lithuania, agrees that Meta's response times vary greatly, claiming it can take months before the platform checks and removes content, though they say eventually most of the content gets removed.

Claudio Tamburrino works at Barzanò & Zanardo, a private consultancy and trusted flagger in Italy focusing on trademark fraud. While they don’t specifically focus on investment scams, he says that reporting content works effectively on platforms such as Temu and TikTok, whereas Meta ones often take much longer. According to Tamburrino, Barzanò & Zanardo, along with other trusted flaggers interviewed for this piece, believe that Meta’s reporting mechanism is largely managed by chatbots, and that only repeated removal requests are eventually handled by the company’s human moderators. However, most content they flag is eventually removed, he says.

“They're using the functionality of the platforms to just get your contact details, and then everything moves off the platform.”

— Paul O'Brien, Bank of Ireland

At the same time, AI is turbocharging the game of cat-and-mouse between advertisers and watchdogs. “There are often several versions of the same advertisement, and the fraudulent one is hidden somewhere in the middle. This is done deliberately to make it more difficult – also for us, because the [detection system] doesn't catch all the variants.,” says Auer.

Worse still, as several sources familiar with moderation content confirmed, even when ads are removed, they often reappear in slightly altered form, forcing the entire process to start over. According to the Bank of Ireland’s Paul O’Brien, AI-cloned investment fraud has gotten more sophisticated with every passing week. “Within one specific ad, there are now about 50+ different versions of the same ad from the same advertiser, slightly different, but essentially doing the same thing or bringing you to the same place.”

The scam advertisers will deliberately activate one ad for just a few hours at a time, before deactivating it and using another version, O’Brien says, to evade detection from flaggers and automated screening systems. “They're using the functionality of the platforms to just get your contact details, and then everything moves off the platform,” he explains.

Worse still, as several sources familiar with moderation content confirmed, even when ads are removed, they often reappear in slightly altered form, forcing the entire process to start over. According to the Bank of Ireland’s Paul O’Brien, AI-cloned investment fraud has gotten more sophisticated with every passing week. “Within one specific ad, there are now about 50+ different versions of the same ad from the same advertiser, slightly different, but essentially doing the same thing or bringing you to the same place.”

The scam advertisers will deliberately activate one ad for just a few hours at a time, before deactivating it and using another version, O’Brien says, to evade detection from flaggers and automated screening systems. “They're using the functionality of the platforms to just get your contact details, and then everything moves off the platform,” he explains.

Prosecutors and police can’t keep up

For seven years, German public prosecutor Nino Goldbeck has been hunting large scam syndicates, the operators behind the fraudulent online platforms. When the Bavarian Central Office for Cybercrime created its own department for economic cybercrime in late 2018, where Goldbeck and just one colleague investigated investment scams. “We had no idea of the scale this would take on,” he says.Goldbeck now heads two departments alongside another senior prosecutor, together employing 12 prosecutors. He estimates that in Germany alone, fraudulent online trading causes losses in the billions every year. His team can receive up to 40 complaints in a single day, but bringing cases to court can often take years.

In July, a trial began at the Bamberg regional court involving two men accused of defrauding German investors of over half a million euros from a call centre in Bulgaria. The alleged scam stemmed from 2018. Inside the courtroom, the prosecutor took several minutes to read out the names of all the victims who for months transferred money to a supposed trading platform in the hopes of a big payoff. Victims testified to the court how the men urged them to continually give more and more money.

Such long investigations are the norm for Goldbeck’s team. Victims usually provide only sparse clues, he says. Names of platforms or supposed employees are often untraceable, hiding behind fake companies within shell companies offshore. Their trail regularly leads them to the Balkans, he explains, home to many call centres, often the epicentre of large-scale fraudulent investment schemes.

There are so many that not every alleged scam can be brought to trial, or have every victim heard. “We have to prioritise,” says Goldbeck. “There are certain people we focus on because the evidence is strong. In those cases, the provable damages are particularly high. That’s where we have really solid material.” With his team, Goldbeck has already dismantled numerous networks.

In Ireland, Detective Superintendent Michael Cryan says law enforcement has seen a 21 per cent surge in investment fraud reports just in the last three months. A recent press release issued a warning to Irish residents of a rise in fake advertisements across popular online platforms, where the scams promote “fake ‘bond’ or ‘deposit’ products using convincing documentation and branding.” Last year victims lost over €30 million to investment fraud, with the police warning that investment fraud “continues to be a major area of criminal activity across Ireland.”

Andre Hvoslef-Eide, a public prosecutor in Norway’s economic and environmental crime unit Økokrim, describes the development of reported digital financial offences in his country over the last 10 years as "dramatic", with over 30,000 reported cases last year. "We are approaching 1000 cases per week,” he says, adding that investigating every complaint would be impossible given the limited resources. "In Europe, we see trends… and reports indicating that money is being used to finance violent crime,” he says. “We suspect that the proceeds of fraud have now replaced earnings from the sale of drugs in the criminal networks.”

“We suspect that the proceeds of fraud have now replaced earnings from the sale of drugs in the criminal networks.”

— Andre Hvoslef-Eide, Norway public prosecutor

EU tech law leaves fraud unchecked

When the Digital Services Act was introduced in 2022, it was hailed as a landmark law reining in Big Tech in Europe. Large platforms found to have breached it by the European Commission can be fined up to 6 per cent of their annual global turnover. From its inception, consumer watchdogs have lamented what they see as shortcomings in tackling illegal or harmful online content.When it comes to dealing with online scam content, one part of the text has significant implications. Article 8 states that there is “no general obligation“ for companies such as Meta and Google to monitor content published by third parties.

Similar to under Section 230 of the US Communications Decency Act, this means platforms cannot be held liable for content they host. On paper, this clause is designed to protect freedom of speech on the internet, mitigating risks of government censorship or interference. In practice, it means platforms do not police illegal content, though they must have mechanisms in place to ensure content is reasonably reviewed.

For Paul O’Brien, Head of Financial Crime Intelligence at the Bank of Ireland, the way the law is written and implemented means action on scam content comes too late. “Our view on the DSA is that it's all about dealing with fraudulent ads after the fact,” he says. “The potential liability for platforms comes where there is a financial loss that is directly attributed to some content that was notified or reported to the platforms, and they didn't take it down.” But, he adds, “to be brutally honest, that's pointless.” Consumers can rarely pinpoint the specific ad post they saw, and even when they can it often happened months ago, he explains.

The Banking and Payments Federation Ireland, of which the Bank of Ireland is a member, is currently applying to be a trusted flagger. The bank therefore lobbied the government in Dublin to push for an amendment in a different EU law on consumer payment protection, the Payment Services Regulation, which is still under negotiation. The proposed clause would require all very large online platforms and major online search engines to verify advertisers’ identities before publishing ads related to financial services.

Last October, Google introduced such checks in Ireland. According to O’Brien, the move is helping to curb the presence of certain types of investment scam ads on their search engine. “But now,” he says, “those ads have moved over to Meta.” Meta does not require companies to be verified before advertising financial products and services on its site, except in Australia, India, Taiwan and the UK. Advertisers wishing to pay for ads to promote financial products and services require no verification in the EU.

Google told Investigate Europe that it has been using advertiser verification since 2020 to screen companies who post financial services on its platforms. The company says it has removed nearly 200 million suspected scam financial services ads globally.

EU tech chief Henna Virkkunen reported in September that Europeans lose over €4 billion a year in online financial scam ads. Credit: European CommissionCredit: European Commission

For O’Brien, carrying out such checks is not about screening content, which he says EU officials warn could conflict with the Digital Services Act. But the amendment looks unlikely to make it over the line; neither member states (represented by the EU Council) nor the European Parliament are pushing for it, documents setting out their negotiating positions show.

Despite O’Brien’s misgivings, the European Commission still sees its tech law as up to the task. “The fight against financial scams is complex and cross-border. But with the DSA, Europe now has the tools to push platforms to act before harm is done,” European Commissioner Virkkunen said this month.

Asked whether a fully implemented DSA could tackle the issue, a spokesperson for the EU executive branch pointed to the ongoing investigation into Meta, as well as the recent overtures to Apple, Google and Microsoft. “The European Commission is actively monitoring the issue of deceptive advertising, including in relation to financial scams,” a spokesperson told Investigate Europe.

Back in Vienna, Valentine Auer says the problem is far beyond what trusted flaggers can deal with, particularly since Meta’s decision in January to end its third-party fact-checking system. “We assume that Meta is technically able to stop most of these ads,” the researcher says. “The same images are blocked immediately if uploaded as a private post. But as paid adverts," she says, “they just keep running.” The researcher sighs. “It is clear that business comes first.”

Meta did not respond to requests for comment by the time of publication.

------ Additional reporting: Amund Trellevik, Marta Portocarrero Coordination: Mei-Ling McNamara Editing: Ella Joyner, Chris Matthews Fact-checking: Ella Joyner

This story is part of Scam Europe, an investigation project led and coordinated by Investigate Europe and the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. The series is being published with media partners including Altreconomia, Balkan Insight, EU Observer, The Irish Times, La Libre, Netzpolitik.org, Público and Der Standard.

IJ4EU (Investigative Journalism for Europe) IJ4EU (Investigative Journalism for Europe) provided funding support for the investigation.

Despite O’Brien’s misgivings, the European Commission still sees its tech law as up to the task. “The fight against financial scams is complex and cross-border. But with the DSA, Europe now has the tools to push platforms to act before harm is done,” European Commissioner Virkkunen said this month.

Asked whether a fully implemented DSA could tackle the issue, a spokesperson for the EU executive branch pointed to the ongoing investigation into Meta, as well as the recent overtures to Apple, Google and Microsoft. “The European Commission is actively monitoring the issue of deceptive advertising, including in relation to financial scams,” a spokesperson told Investigate Europe.

Back in Vienna, Valentine Auer says the problem is far beyond what trusted flaggers can deal with, particularly since Meta’s decision in January to end its third-party fact-checking system. “We assume that Meta is technically able to stop most of these ads,” the researcher says. “The same images are blocked immediately if uploaded as a private post. But as paid adverts," she says, “they just keep running.” The researcher sighs. “It is clear that business comes first.”

Meta did not respond to requests for comment by the time of publication.

------ Additional reporting: Amund Trellevik, Marta Portocarrero Coordination: Mei-Ling McNamara Editing: Ella Joyner, Chris Matthews Fact-checking: Ella Joyner

This story is part of Scam Europe, an investigation project led and coordinated by Investigate Europe and the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. The series is being published with media partners including Altreconomia, Balkan Insight, EU Observer, The Irish Times, La Libre, Netzpolitik.org, Público and Der Standard.

IJ4EU (Investigative Journalism for Europe) IJ4EU (Investigative Journalism for Europe) provided funding support for the investigation.