Alexia Barakou

Alexia Barakou

European Union plans for a circular plastic economy are failing. Countries still ship their plastic waste, burn it and dump it in landfills. The plastic industry, meanwhile, continues to wield its influence and push against initiatives.

Kenneth Bruvik has for years collected plastic waste along the Norwegian west coast. Standing on the shore on a cold April morning, he remembered the first time he came to the small beach outside Bergen. “I cried,” he says, recalling the sight of tonnes of bottles, carrier bags and other single-use plastics crammed among the rocks. Piles of it churned into such small pieces that it stuck like glitter to his shoes.

Ironically, it’s mostly not Norway’s waste, where the plastic collection system works well – but that doesn’t help much if others continue to pollute. Some of the plastic here comes from Asia, some from North America. But most comes from Europe. “To everyone who produces these single-use bottles: stop it!”, he urges, standing on a heap of plastic bottle litter.

Ironically, it’s mostly not Norway’s waste, where the plastic collection system works well – but that doesn’t help much if others continue to pollute. Some of the plastic here comes from Asia, some from North America. But most comes from Europe. “To everyone who produces these single-use bottles: stop it!”, he urges, standing on a heap of plastic bottle litter.

Kenneth Bruvik collects plastic waste around Bergen’s coastline.Amund Trellevik

A few thousand kilometres south, at a waste recovery facility north of Athens, workers are busy opening containers of rubbish. Plastic waste that went into yellow cargoes across Germany three years ago is now surfacing in Greece (it was previously sent to Turkey for recycling). Thirty-seven containers have been stuck in Piraeus port since the end of 2021, after failed attempts by Turkey to ship them to Vietnam. “This is rubbish that is impossible to recycle,” says Yannis Polychronopoulos, who owns the firm that took on the task of emptying the cases.

This dumping ground deadlock is indicative of a European failure to deal with a mounting plastic problem, where seas and coastlines are polluted, illegal waste sites are rife and hazardous landfills and incineration plants abound. And while promises of recycling and reuse are boasted about in Brussels and industry boardrooms, Investigate Europe research reveals how Europe’s plans for plastic are failing – and its circular economy is leaking.

“We need to kill the illusion that these things are recycled,” says Nusa Urbancic, campaigns director at the international foundation Changing Markets. “It’s a very different feeling when you know that the plastic you bought things in is not recycled but ends up in a landfill or being incinerated.”

This dumping ground deadlock is indicative of a European failure to deal with a mounting plastic problem, where seas and coastlines are polluted, illegal waste sites are rife and hazardous landfills and incineration plants abound. And while promises of recycling and reuse are boasted about in Brussels and industry boardrooms, Investigate Europe research reveals how Europe’s plans for plastic are failing – and its circular economy is leaking.

A not-so circular waste economy

From yoghurt pots and milk cartons to shampoo bottles and toothpaste tubes, Europeans produce an average of 35kg of plastic packaging waste each per year. And the trend is rising. According to the OECD, plastic consumption will triple by 2060. Contrary to what many assume, most packaging is not recycled. Instead, it ends up in landfills or potentially toxic incinerators. It is estimated that at most 40 per cent of plastic packaging generated across Europe is recycled.“We need to kill the illusion that these things are recycled,” says Nusa Urbancic, campaigns director at the international foundation Changing Markets. “It’s a very different feeling when you know that the plastic you bought things in is not recycled but ends up in a landfill or being incinerated.”

Given the limitations and lack of recycling, a huge demand for new plastic remains, bringing with it dramatic consequences. Plastic is made from oil and gas, fossil fuels that drive the climate crisis. Researchers in the United States predict plastic production and disposal will cause 15 per cent of global CO2 emissions by 2050. It is also accelerating an unprecedented environmental catastrophe. European and US studies recently calculated that 11 million tonnes of plastic waste flow into the world’s oceans annually. By 2030, it could be twice as much – if politicians, business and people do not act.

Back in 2015, the EU presented an action plan for a circular economy. Then Commission Vice-President and now Climate Action Commissioner Frans Timmermans vowed to “close the loop”. In the future, they say, raw materials like plastic should circulate endlessly. From production to the supermarket, on to the dining table, into the rubbish bin and back to the recycling plant. The latest in a string of EU initiatives to curb our plastic craze was the boldest yet.

Back in 2015, the EU presented an action plan for a circular economy. Then Commission Vice-President and now Climate Action Commissioner Frans Timmermans vowed to “close the loop”. In the future, they say, raw materials like plastic should circulate endlessly. From production to the supermarket, on to the dining table, into the rubbish bin and back to the recycling plant. The latest in a string of EU initiatives to curb our plastic craze was the boldest yet.

Sixty per cent of Europe’s plastic packaging waste is not recycled.Shutterstock

But as new research by Investigate Europe documents, efforts to build a circular economy are failing. Visiting recycling plants, incinerators and landfills from Portugal to France and from Greece to Poland, the research has found:

Poland, described by some as the “waste dump of Europe”, is a particular hotspot. In the town of Wschowa, not far from the German border, an entrepreneur’s sand mining business caught the attention of authorities after locals complained of rancid smells coming from the fields. Court documents show that Zbigniew T. (his full name cannot be used), made his fortune not from selling sand but by burying thousands of tonnes of illegal waste from Germany and western Poland. His profits ran into millions of (untaxed) zlotys.

- 60 per cent of plastic packaging waste in Europe is still not recycled. Millions of tonnes end up in landfill and incineration plants. Much of it by design cannot be recycled.

- Dozens of new incineration plants are planned across Europe, stoking ecological concerns over toxic pollutants. The burning of waste in Europe jumped 40 per cent between 2018 and 2020.

- Governments allow plastic producers and multinational brands to influence waste management schemes and be the brokers between municipalities, recyclers and incineration operators.

- Brands that use plastic packaging are obliged to finance the recycling of their waste. But many are leaving local municipalities and taxpayers footing much of the bill.

- Underfunded authorities are ill-equipped to combat the growing number of illegal waste operations across the continent.

Waste trafficking: high earnings with low risk

For a long time, European countries managed their plastic waste far out of sight, officially to be recycled. But since Asian countries, above all China, banned such imports in 2018, much more used plastic now travels across Europe. Despite gaps in official data, EU countries shipped 2.5 million tonnes of plastic waste back and forth in 2021. This waste often ends up not in recycling plants, but in illegal landfills.Poland, described by some as the “waste dump of Europe”, is a particular hotspot. In the town of Wschowa, not far from the German border, an entrepreneur’s sand mining business caught the attention of authorities after locals complained of rancid smells coming from the fields. Court documents show that Zbigniew T. (his full name cannot be used), made his fortune not from selling sand but by burying thousands of tonnes of illegal waste from Germany and western Poland. His profits ran into millions of (untaxed) zlotys.

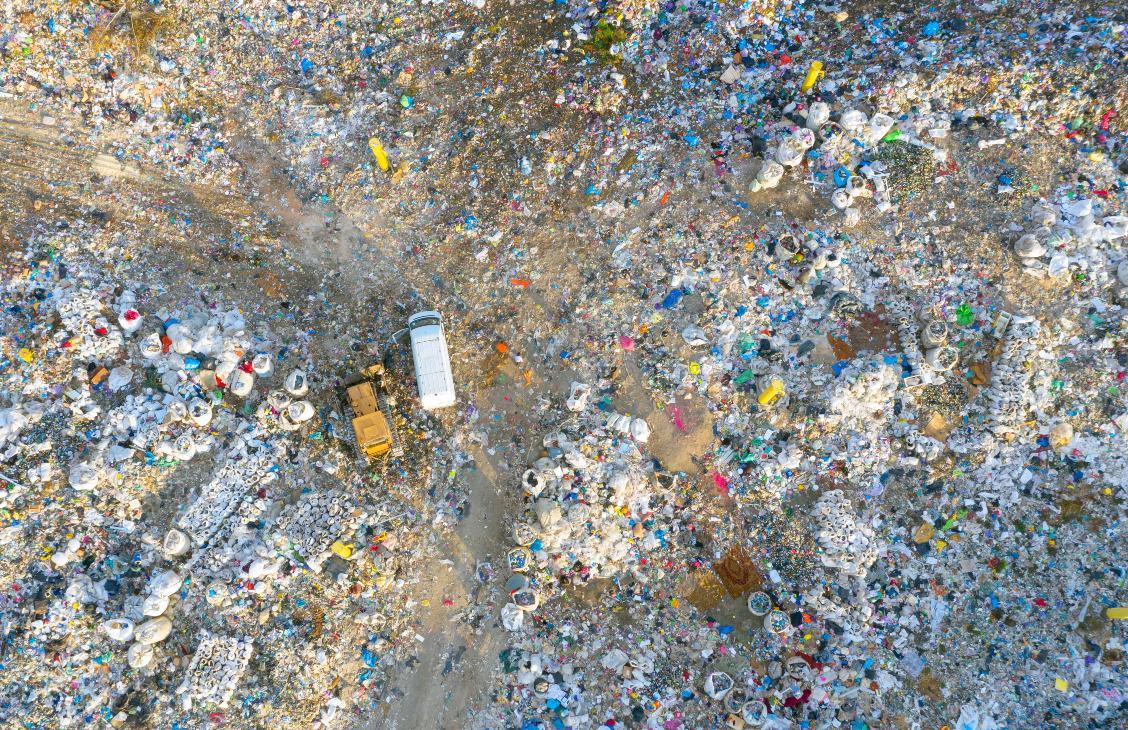

A plastic dump site in Poland, where illegal waste operations are increasingly common.Shutterstock

The sand and gravel holes operated by his firm were several hundred metres deep, and prosecutors allege they were filled with almost half a million cubic metres of waste – enough to fill around 5000 large trucks.

One of Poland’s biggest illegal waste trials is still ongoing, but the German company whose waste was discovered there has so far been left untouched by inspectors. The UK, though, was forced in 2020 to take back hundreds of tonnes of waste found to have been illegally sent to Poland. Italy, itself a hive for the illegal waste trade, has faced similar demands.

The price received per tonne of illegal waste from the West fluctuates between €30 and €50 in Poland, far cheaper than pursuing legitimate routes to recycling facilities in Germany, which could cost €300 per tonne. Dumping waste in a landfill in the UK can cost €113 per tonne, more than double that in Poland, Romania, Bulgaria or Croatia where illegal sites have sprung up in recent years.

The case of Zbigniew T. is among the handful that go to court. Authorities publicise hundreds of inspections, but only a few dozen waste-related cases reach prosecutors’ offices in Poland each year, a country of 38 million people.

Agencies are often woefully understaffed. Portugal only has 30 inspectors responsible for investigating environmental crimes in the country. They cover all the territory, visiting production sites, checking dumps, controlling national borders. Their salaries are low, compared to other civil servants, with senior officials earning less than €3,800 per month. The same problem exists in Poland, where inspectors are leaving for better paid jobs in the private sector.

One of Poland’s biggest illegal waste trials is still ongoing, but the German company whose waste was discovered there has so far been left untouched by inspectors. The UK, though, was forced in 2020 to take back hundreds of tonnes of waste found to have been illegally sent to Poland. Italy, itself a hive for the illegal waste trade, has faced similar demands.

The price received per tonne of illegal waste from the West fluctuates between €30 and €50 in Poland, far cheaper than pursuing legitimate routes to recycling facilities in Germany, which could cost €300 per tonne. Dumping waste in a landfill in the UK can cost €113 per tonne, more than double that in Poland, Romania, Bulgaria or Croatia where illegal sites have sprung up in recent years.

The case of Zbigniew T. is among the handful that go to court. Authorities publicise hundreds of inspections, but only a few dozen waste-related cases reach prosecutors’ offices in Poland each year, a country of 38 million people.

Inspection inefficiencies

Investigations are often thankless, costly endeavors. Penalties are small and the chance of catching the real perpetrators is low. The list of problems faced by inspectors is long: member states assign waste differently, there are no inspection standards, there is a lack of reliable data and no centralised electronic information exchange exists.Agencies are often woefully understaffed. Portugal only has 30 inspectors responsible for investigating environmental crimes in the country. They cover all the territory, visiting production sites, checking dumps, controlling national borders. Their salaries are low, compared to other civil servants, with senior officials earning less than €3,800 per month. The same problem exists in Poland, where inspectors are leaving for better paid jobs in the private sector.

To exchange key information, the EU wants to use IMSOC, the information management system for official inspections. It already contains information on, for example, unsafe food or feed, but it is currently only used by 32 out of 148 countries. The EU Commission wants to tighten rules to prevent the illegal waste trade between countries, with a revised Waste Shipment Regulation (WSR) planned for 2025.

In recent years, the EU has funded several programs to help member states connect and deal with waste, but the impact has been minimal. Operation Demeter, meanwhile, which targets all kinds of illegal hazardous waste globally with ad-hoc actions including in the EU, seized almost 4000 tonnes of waste during its latest campaign in October.

This is despite the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), a mechanism supposed to make polluters pay for the full life cycle of the product, from production, via consumption, to waste, and to recycling into raw material for new plastic.

In recent years, the EU has funded several programs to help member states connect and deal with waste, but the impact has been minimal. Operation Demeter, meanwhile, which targets all kinds of illegal hazardous waste globally with ad-hoc actions including in the EU, seized almost 4000 tonnes of waste during its latest campaign in October.

Plastic producer failures

While illegal operations go largely unchecked, legitimate producers continue to help compound Europe’s plastic waste problem. Brands that wrap their products in plastic have a central role in the waste management process. But they don’t have any powerful incentive to reduce the use of new plastic.This is despite the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), a mechanism supposed to make polluters pay for the full life cycle of the product, from production, via consumption, to waste, and to recycling into raw material for new plastic.

Plastic and other household waste piled up on the streets of Paris.Shutterstock

Germany, France, Italy and the Netherlands put this noble principle into practice in the late 1990s, but they focused on the end-of-life part. When the EU Commission took up the EPR concept in its 2008 Waste directive, it also called on governments “to encourage the design of products in order to reduce their environmental impacts” – 80 per cent of the recyclability of packaging happens in the design phase.

But there were no mandatory targets or penalties for those using several plastics in their bottles or boxes, making them unrecyclable. “Actions to prevent waste have been missing for 20 years. Instead, we have fully concentrated on recycling,” says Helmut Maurer, a former senior expert in the European Commission’s directorate for circular economy.

The main Norwegian producers’ organisation rewards companies that voluntarily reduce packaging. But this is not the general European pattern.

But there were no mandatory targets or penalties for those using several plastics in their bottles or boxes, making them unrecyclable. “Actions to prevent waste have been missing for 20 years. Instead, we have fully concentrated on recycling,” says Helmut Maurer, a former senior expert in the European Commission’s directorate for circular economy.

The main Norwegian producers’ organisation rewards companies that voluntarily reduce packaging. But this is not the general European pattern.

A powerful lobby

Producer responsibility organisations (PROs), often non-profit groups controlled by industry, are charged with implementing the scheme. Packaging producers and brands that use plastic packaging are PRO members. Members pay a fee to the PRO for every tonne they put on the market. Strategically placed between municipalities that collect waste and recycling businesses, PROs are powerful players in plastic waste systems.“From an efficiency point of view, it is logical to have a single place where you collect data, recycle, and manage incinerators,” explains Janine Röling from the Dutch NGO Recycling Netwerk. “But in reality, PROs have become lobby groups representing producers’ interests.”

A waste sorting facility in Hungary. Plastic producers are meant to help with the costs of plastic collection and recycling.Attila Kalman

PRO fees are calculated from the amount of packaging put on the market while selling bottled water, soft drinks or confectioneries. The money is supposed to fund local waste collection and help accelerate recycling processes. As PROs are often monopolies, they tend to have the upper hand in negotiations. Municipalities around Europe claim they are not compensated enough, which leaves taxpayers footing part of the bill.

Citeo, France’s main PRO, counts industry giants Coca-Cola, Danone, L’Oréal, and Carrefour among its members. It is obliged by the government to cover 80 per cent of collecting and recycling costs borne by authorities. Yet municipalities often disagree with the calculation. Amorce, a national municipalities association, has said Citeo reimburses at most 40 per cent of their costs – a funding shortfall of €1 billion.

Municipalities in Norway also complain: “We pay more than one billion NOK (around €89 million) per year for handling of plastic packaging waste that the producers should have financed,” claims Svein Kamfjord, director at Samfunnsbedriftene, an umbrella organisation for public waste companies. Plastretur, Norway’s major PRO, says the compensation is correct as of now, and “the result of agreements with the municipalities”. However, Plastretur supports the demand from municipalities that authorities define clearly how the EU regulation on who will pay what, is to be interpreted in Norway, according to CEO Karl Johan Ingvaldsen.

In Spain, the Balearic Islands’ government carried out two studies that question the official figures from Ecoembes, the Spanish PRO. One report stated that in 2016 its members declared that 49,385 tonnes of light packaging was placed on the market in that autonomous community, while the analysis of packaging flows along the entire value chain placed that figure at 91,965 tonnes. If the Balearic government’s calculations were true, it would mean that the packaging placed on the market was 86% more than that declared by producers.

“The data provided by Ecoembes is impossible. They are not at all credible claims,” say Vicenç Vidal, member of the Spanish senate, who ordered the reports when an environment councillor in the Balearic government. Ecoembes says there were “serious methodological deficiencies” and that subsequent studies refuted its data.

Citeo, France’s main PRO, counts industry giants Coca-Cola, Danone, L’Oréal, and Carrefour among its members. It is obliged by the government to cover 80 per cent of collecting and recycling costs borne by authorities. Yet municipalities often disagree with the calculation. Amorce, a national municipalities association, has said Citeo reimburses at most 40 per cent of their costs – a funding shortfall of €1 billion.

Municipalities in Norway also complain: “We pay more than one billion NOK (around €89 million) per year for handling of plastic packaging waste that the producers should have financed,” claims Svein Kamfjord, director at Samfunnsbedriftene, an umbrella organisation for public waste companies. Plastretur, Norway’s major PRO, says the compensation is correct as of now, and “the result of agreements with the municipalities”. However, Plastretur supports the demand from municipalities that authorities define clearly how the EU regulation on who will pay what, is to be interpreted in Norway, according to CEO Karl Johan Ingvaldsen.

Underreporting favours producers

PROs collect data on the volume of plastics put on the market by producers and brands. Authorities largely depend on this data when calculating the countries’ recycling rates.In Spain, the Balearic Islands’ government carried out two studies that question the official figures from Ecoembes, the Spanish PRO. One report stated that in 2016 its members declared that 49,385 tonnes of light packaging was placed on the market in that autonomous community, while the analysis of packaging flows along the entire value chain placed that figure at 91,965 tonnes. If the Balearic government’s calculations were true, it would mean that the packaging placed on the market was 86% more than that declared by producers.

“The data provided by Ecoembes is impossible. They are not at all credible claims,” say Vicenç Vidal, member of the Spanish senate, who ordered the reports when an environment councillor in the Balearic government. Ecoembes says there were “serious methodological deficiencies” and that subsequent studies refuted its data.

Spain’s PRO is one of several that has allegedly uderreported the amount of plastic packaging put on the market.Shutterstock

Companies that produce or use plastic packaging are obliged to be members of a PRO and pay EPR fees. But many don’t. “Free-riding is a huge problem, in some countries it is five per cent to 10 per cent, in others it is up to 50 per cent,” says Joaquim Quoden, managing director of EXPRA, Europe’s Extended Producers Responsibility Alliance.

“There will be a bit of a smell here,” says the director of Hungary’s only incinerator, Tamás Jászay, opening a door into the so-called waste bunker: several stories high, it’s the dumping ground for Budapest’s rubbish, from which pigeons peck before it is swallowed by concrete furnaces burning at nearly a thousand degrees. The four furnaces here burn an average of 1,000 tonnes of plastic and other waste a day. At the end there is nothing left apart from slag that is carried away by waiting trucks, and carbon dioxide rising silently up the chimney.

Incineration heats up

The more plastic produced by manufacturers, the more there is to dispose of. Although recycling capacity is expanding, plastic waste is increasingly being sent to incineration plants. This is largely due to ever-growing consumption. But it is also a result of China’s plastic waste import ban in 2018. In the following two years, the amount of waste incinerated in the EU increased 39 per cent.“There will be a bit of a smell here,” says the director of Hungary’s only incinerator, Tamás Jászay, opening a door into the so-called waste bunker: several stories high, it’s the dumping ground for Budapest’s rubbish, from which pigeons peck before it is swallowed by concrete furnaces burning at nearly a thousand degrees. The four furnaces here burn an average of 1,000 tonnes of plastic and other waste a day. At the end there is nothing left apart from slag that is carried away by waiting trucks, and carbon dioxide rising silently up the chimney.

The ecological impact of incineration was recently analysed by Dutch toxicologist Abel Arkenbout, who was commissioned by several NGOs to investigate possible pollution around plants in France, Spain, Lithuania and the Czech Republic. The December study found: “Increased amounts of hazardous persistent organic pollutants were also found in vegetation in the vicinity of the waste incinerators.”

Nearly 500 plants across Europe burnt household waste in 2020, according to industry association CEWEP. Facilities emit 300 kilograms of residue per tonne of waste incinerated. These dusts and remnants are sometimes highly toxic.

In Germany construction firms reuse incineration residues to pave new roads. “Waste incineration ash does not do well there,” warns environmental engineer Peter Gebhardt. “Not only in roads, but also in landfills, disposal companies dump some of the residue. Contrary to what is often claimed, incineration plants do not eliminate waste dumps.”

And they are growing in number. There are plans for 39 new plants in Poland. So far, the country has 10. They could potentially be co-financed by the European Investment Bank, which has allocated €1.3 billion for the construction of new incinerators. In the Czech Republic, five new plants are to be built. This would give the country an annual incineration capacity of 2.2 million tonnes.

Nearly 500 plants across Europe burnt household waste in 2020, according to industry association CEWEP. Facilities emit 300 kilograms of residue per tonne of waste incinerated. These dusts and remnants are sometimes highly toxic.

In Germany construction firms reuse incineration residues to pave new roads. “Waste incineration ash does not do well there,” warns environmental engineer Peter Gebhardt. “Not only in roads, but also in landfills, disposal companies dump some of the residue. Contrary to what is often claimed, incineration plants do not eliminate waste dumps.”

And they are growing in number. There are plans for 39 new plants in Poland. So far, the country has 10. They could potentially be co-financed by the European Investment Bank, which has allocated €1.3 billion for the construction of new incinerators. In the Czech Republic, five new plants are to be built. This would give the country an annual incineration capacity of 2.2 million tonnes.

The incineration plant in Brescia, Italy is one of around 500 facilities across Europe.Lorenzo Buzzoni

The average life-span of an incinerator is about 25 years, and some municipalities that already have them are obliged to provide a fixed amount of waste or face high penalties. As a result, municipalities have little incentive to sort and recycle waste more thoroughly. “Imagine that they dutifully separate their waste and end up being sued,” says Janek Vähk, who studies the issues for the NGO Zero Waste Europe.

The incineration business threatens to become less lucrative from 2028, however. The EU will then include the plants in the European Emissions Trading Scheme, forcing plants to pay for their greenhouse gases emissions. But incineration plants will still burn plastic in the future. One reason for this is the packaging itself.

His company is importing waste from France, the Netherlands and Switzerland and Norway. Last year 10,500 tonnes, almost 10 per cent of the plastic waste his plant recycles, came from Norway. “This material is basically cleaner,” says Stechert. “From that, we try to recycle as many waste fractions as possible.”

The reason why only part of the plastic can often be recycled in plants like this, is design. A bottle of ketchup or shampoo, for instance, could consist of three or four types of different plastic. These cannot be melted together, as they have different melting points. Consequently, they can only be incinerated or sent to landfill.

The incineration business threatens to become less lucrative from 2028, however. The EU will then include the plants in the European Emissions Trading Scheme, forcing plants to pay for their greenhouse gases emissions. But incineration plants will still burn plastic in the future. One reason for this is the packaging itself.

‘Truly circular design’

On the southern edge of the Westhavelland Nature Park, an hour’s drive from Berlin, Michael Stechert pulls a shopping bag out of a man-sized plastic bale in the Vogt recycling plant yard. Pressed into the bale are scampi containers, Schweppes bottles and sweet wrappers.His company is importing waste from France, the Netherlands and Switzerland and Norway. Last year 10,500 tonnes, almost 10 per cent of the plastic waste his plant recycles, came from Norway. “This material is basically cleaner,” says Stechert. “From that, we try to recycle as many waste fractions as possible.”

The reason why only part of the plastic can often be recycled in plants like this, is design. A bottle of ketchup or shampoo, for instance, could consist of three or four types of different plastic. These cannot be melted together, as they have different melting points. Consequently, they can only be incinerated or sent to landfill.

Bales of plastic waste at the Vogt recycling facility near Berlin.Nico Schmidt

To close the cycle, the composition of the packaging must be changed. But so far, the opposite is happening. “The industry has increased the quantity of cheap flexible and multi-layered plastics,” the consulting firm Changing Markets wrote in a recent report. In an open letter, several NGOs, including the European Environmental Bureau and Zero Waste Europe called for “a truly circular design that prepares plastics for reuse and recycling.”

Industry is protesting mandatory targets for this which the EU Commission proposes. But even if the measures prevail, that is not enough, says former EU Commission plastics expert Helmut Maurer. He believes the price of packaging must be increased to reflect its climate and environmental impact, thus incentivising people to “produce as little waste as possible”.

Maurer, and many like him, say ultimately the waste loop dreamed of by the EU must become smaller. “The real answer must be to avoid plastic waste.”

That would be the start of a path to a smaller circular economy with less produced and from which less plastic would leak. Then, Greek harbour workers would not have to dispose of illegal shipments from Germany, and Kenneth Bruvik would be able to walk along the Norwegian coastline without dodging plastic debris.

Editors: Ingeborg Eliassen, Chris Matthews & Elisa Simantke

Industry is protesting mandatory targets for this which the EU Commission proposes. But even if the measures prevail, that is not enough, says former EU Commission plastics expert Helmut Maurer. He believes the price of packaging must be increased to reflect its climate and environmental impact, thus incentivising people to “produce as little waste as possible”.

Maurer, and many like him, say ultimately the waste loop dreamed of by the EU must become smaller. “The real answer must be to avoid plastic waste.”

That would be the start of a path to a smaller circular economy with less produced and from which less plastic would leak. Then, Greek harbour workers would not have to dispose of illegal shipments from Germany, and Kenneth Bruvik would be able to walk along the Norwegian coastline without dodging plastic debris.

Editors: Ingeborg Eliassen, Chris Matthews & Elisa Simantke