.jpg&w=3840&q=75)

Alexia Barakou

26 October 2023 Lorenzo Buzzoni

Lorenzo Buzzoni Nico Schmidt

Nico Schmidt

Needed for speed: European carmakers turn to mining to bypass China

.jpg&w=3840&q=75)

Alexia Barakou

Needed for speed: European carmakers turn to mining to bypass China

26 October 2023In an effort to become independent of Chinese suppliers, Western automotive executives are making bold strategic moves. They are abandoning conventional supply chains and instead committing huge sums to form direct partnerships with mining firms.

Six kilometres from the Chilean border in San Juan, Argentina, the drilling machine shakes the earth and raises a cloud of dust. A pounding noise spreads across the peaks of the Andes. At an altitude of 3500 metres, more than a hundred holes have been opened here in search of copper.

The Los Azules site is one of eight major copper projects recently launched in Argentina amid booming global demand for the red metal, essential for electric cars. Only a few years ago, the last copper mine was being closed in Argentina. Now, thanks to car firms like Stellantis, which signed a $155 million deal to secure some of the 100,000 tonnes of copper per year, the drills are back to shatter the silence in the mountains.

Europe’s green transition depends on a massively increased supply of minerals, such as copper and lithium. Sixty per cent of the assessed need comes from the transportation sector, according to an industry-commissioned study. The car industry is driving this process, as they are required to make all cars zero emission by 2035.

The stakes could not be higher: without a stable supply of lithium, European carmakers face insurmountable obstacles in building the essential batteries for their electric SUVs and sedans. As a result, assembly lines in Turin or Wolfsburg could grind to a halt. Potentially changing the trajectory of the entire automotive landscape.

The car industry is at a turning point. For a long time, it relied on a stable supply chain from China. Whether the raw materials would arrive was not a major concern for executives. They were more concerned about the price of the parts produced. In 2016, Matthias Mueller, then Volkswagen’s CEO, described plans for the company’s own battery factories as "nonsense". His company would certainly not do such a thing because it would be "so expensive".

Since then, Volkswagen has begun planning several battery factories, from Ontario in Canada to Wolfsburg in northern Germany.

The Los Azules site is one of eight major copper projects recently launched in Argentina amid booming global demand for the red metal, essential for electric cars. Only a few years ago, the last copper mine was being closed in Argentina. Now, thanks to car firms like Stellantis, which signed a $155 million deal to secure some of the 100,000 tonnes of copper per year, the drills are back to shatter the silence in the mountains.

Europe’s green transition depends on a massively increased supply of minerals, such as copper and lithium. Sixty per cent of the assessed need comes from the transportation sector, according to an industry-commissioned study. The car industry is driving this process, as they are required to make all cars zero emission by 2035.

The stakes could not be higher: without a stable supply of lithium, European carmakers face insurmountable obstacles in building the essential batteries for their electric SUVs and sedans. As a result, assembly lines in Turin or Wolfsburg could grind to a halt. Potentially changing the trajectory of the entire automotive landscape.

The car industry is at a turning point. For a long time, it relied on a stable supply chain from China. Whether the raw materials would arrive was not a major concern for executives. They were more concerned about the price of the parts produced. In 2016, Matthias Mueller, then Volkswagen’s CEO, described plans for the company’s own battery factories as "nonsense". His company would certainly not do such a thing because it would be "so expensive".

Since then, Volkswagen has begun planning several battery factories, from Ontario in Canada to Wolfsburg in northern Germany.

The Los Azules site is one of eight major copper projects recently launched in Argentina. Stellantis has already struck a deal for its copper.Stellantis

Behind closed doors, industry insiders have long said that without China’s goodwill, the European car industry could scrap its electric future. Batteries in particular consume strategic raw materials, most notably lithium. According to a forecast by the German Raw Materials Agency, global demand for lithium is set to soar in the coming years. From 134,000 tonnes in 2022, demand could rise to 558,800 tonnes in 2030.

"Almost all of the demand for lithium is for batteries," says Leonardo Buizza, a senior analyst at the London-based think tank Energy Transitions Commission. China is the third largest producer of lithium in the world, and has the biggest lithium processing capacity globally. - Making batteries from raw lithium is a complicated and expensive process.

But electric cars need many more critical raw materials than just lithium. Manufacturers are now also using copper, graphite, aluminium, nickel and cobalt in their vehicles. Researchers at the KU Leuven project that the electrification of the automotive industry will account for more than half of global demand for critical raw materials. And China is also heavily involved in most of these supply chains.

But time is pressing. Last week, the Chinese government announced that local graphite exporters will need a permit before taking the raw material out of the country. The regulation is due to take effect in early December and could be a first step towards restricting exports. European carmakers are now trying to wean themselves off their dependence on China. They are investing in mines to secure access to critical raw materials and buying into processing and recycling capacity.

"Almost all of the demand for lithium is for batteries," says Leonardo Buizza, a senior analyst at the London-based think tank Energy Transitions Commission. China is the third largest producer of lithium in the world, and has the biggest lithium processing capacity globally. - Making batteries from raw lithium is a complicated and expensive process.

But electric cars need many more critical raw materials than just lithium. Manufacturers are now also using copper, graphite, aluminium, nickel and cobalt in their vehicles. Researchers at the KU Leuven project that the electrification of the automotive industry will account for more than half of global demand for critical raw materials. And China is also heavily involved in most of these supply chains.

But time is pressing. Last week, the Chinese government announced that local graphite exporters will need a permit before taking the raw material out of the country. The regulation is due to take effect in early December and could be a first step towards restricting exports. European carmakers are now trying to wean themselves off their dependence on China. They are investing in mines to secure access to critical raw materials and buying into processing and recycling capacity.

.png&w=3840&q=75)

Investigate Europe

But can they succeed? Stephane Bourg of the French Geological Survey believes not if it consists in replacing one thermic car by one electric car. The production of the minerals needed for electric cars have not been anticipated enough; it takes more than a decade to open a mine, “not even half of the population will be able to have an electric car with 500 kilometres of reach by 2035,” he tells Investigate Europe during a recent mining event in Athens. “It is impossible in such a timeframe and it is nonsense in terms of sustainability.”

Running electric cars is far greener than petrol or diesel vehicles, but their production – mining for copper, nickel, cobalt and other metals – is far more damaging. Bourg argues that people would have to drive electric cars at the maximum of their capacity for these steep environmental costs to pay off. “With an electric car, the less you drive, the more you pollute,” he says. He believes we must both go full electric and radically rethink transportation, moving away from individual ownership, to ensure electric vehicles are used to the maximum.

In any case, car companies are scrambling for the limited resources there are. The boards of the big car companies are signing agreement after agreement. In mid-March this year, Volkswagen’s Chief Technical Officer, Thomas Schmall, announced that his company would also finance mining in the future. "The bottleneck for raw materials is mining capacity. That’s why we need to invest directly in mines," Schmall said in an interview.

A few months later, it was announced that VW, together with Stellantis, were supporting the purchase of two Brazilian mines for nickel and copper. In the end, the deal fell through because the costs were too high. But the signal was clear.

Running electric cars is far greener than petrol or diesel vehicles, but their production – mining for copper, nickel, cobalt and other metals – is far more damaging. Bourg argues that people would have to drive electric cars at the maximum of their capacity for these steep environmental costs to pay off. “With an electric car, the less you drive, the more you pollute,” he says. He believes we must both go full electric and radically rethink transportation, moving away from individual ownership, to ensure electric vehicles are used to the maximum.

In any case, car companies are scrambling for the limited resources there are. The boards of the big car companies are signing agreement after agreement. In mid-March this year, Volkswagen’s Chief Technical Officer, Thomas Schmall, announced that his company would also finance mining in the future. "The bottleneck for raw materials is mining capacity. That’s why we need to invest directly in mines," Schmall said in an interview.

A few months later, it was announced that VW, together with Stellantis, were supporting the purchase of two Brazilian mines for nickel and copper. In the end, the deal fell through because the costs were too high. But the signal was clear.

Stellantis has signed nine agreements this year to secure its supply chains from mining to processing. (Shutterstock)Shutterstock

Volkswagen is expected to enter into new strategic partnerships in the coming years. (Shutterstock)Shutterstock

It is not yet known where VW intends to extract critical raw materials. The company declined a request for an interview. According to a person involved in the talks, the company has so far rejected an offer to participate in a lithium mining project Vulcan Energy in the Rhine valley.

Stellantis, the multinational which also owns the Peugeot and Fiat brands, is less hesitant. It invested €50 million in Vulcan Energy last year. And this is just one step in the group’s offensive to secure access to raw materials. Already this year, Stellantis has signed nine agreements to secure its supply chains from mining to processing. In Australia, they recently secured 45 kilo tonnes of high purity manganese for battery production. BMW also recently secured lithium from US company Livent for $335 million.

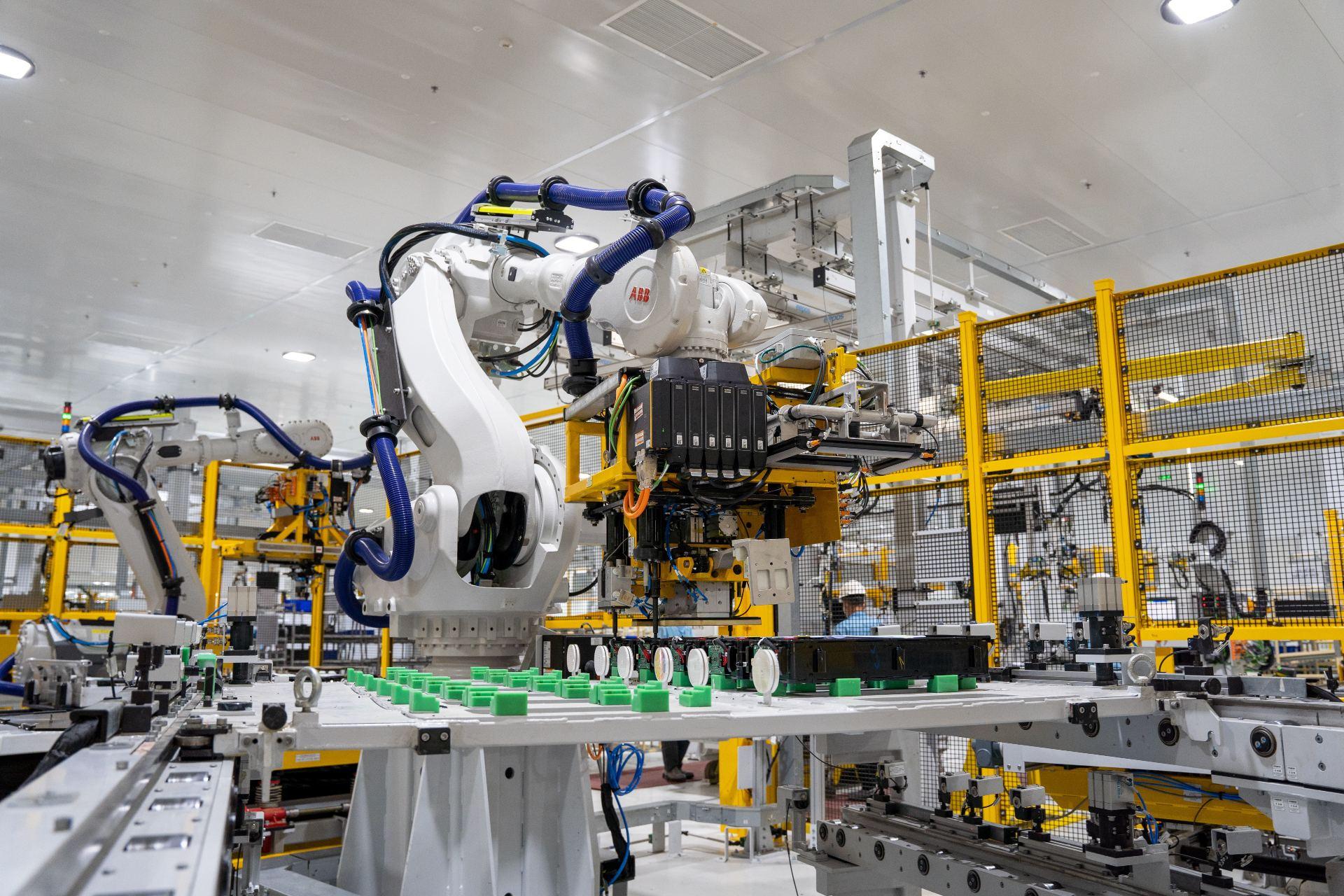

Further down the supply chain, car manufacturers are also investing heavily in battery production.

Together with Mercedes-Benz and TotalEnergies, Stellantis started construction of its first European Gigafactory in France last May. Others are to follow. The company recently announced a "global sourcing strategy". Up to five gigafactories will be built in Europe and North America by 2030. Germany’s Volkswagen Group is also investing heavily in its own battery cell factories, with six gigafactories to be built in Europe alone by 2030.

Stellantis, the multinational which also owns the Peugeot and Fiat brands, is less hesitant. It invested €50 million in Vulcan Energy last year. And this is just one step in the group’s offensive to secure access to raw materials. Already this year, Stellantis has signed nine agreements to secure its supply chains from mining to processing. In Australia, they recently secured 45 kilo tonnes of high purity manganese for battery production. BMW also recently secured lithium from US company Livent for $335 million.

Further down the supply chain, car manufacturers are also investing heavily in battery production.

Together with Mercedes-Benz and TotalEnergies, Stellantis started construction of its first European Gigafactory in France last May. Others are to follow. The company recently announced a "global sourcing strategy". Up to five gigafactories will be built in Europe and North America by 2030. Germany’s Volkswagen Group is also investing heavily in its own battery cell factories, with six gigafactories to be built in Europe alone by 2030.

In Europe, carmakers and their suppliers plan to build at least 46 battery cell factories in the coming years.Shutterstock

In Europe, carmakers and their suppliers plan to build at least 46 battery cell factories with a capacity of more than 1,400 gigawatt hours. At the moment there are only a few gigafactories in Europe with a capacity of around 75 GWh. But how independent carmakers really are from external players, is questionable.

An Investigate Europe analysis found that more than a third of the 46 planned factories will be built and operated by non-European companies. This includes companies from China, such as CATL. The world’s largest manufacturer of lithium-ion batteries plans to produce cells in Erfurt, Germany, and Debrecen in Hungary, for use in Mercedes sports cars.

But Europe’s plans seem dwarfed by China’s, which dominates the world market. By 2021, Chinese factories produced batteries with a capacity of 655 GWh. That is three-quarters of global production.

And it is uncertain how many of the big announcements will actually come to fruition in the end. "The EU’s production capacity is based on manufacturers’ announcements, which are often withdrawn and are not independently verified,” the European Court of Auditors recently warned.

Especially as the massive US subsidy programme, the Inflation Reduction Act, threatens to poach several battery factory projects from Europe. In the first nine months after the US stimulus package came into effect, car and battery manufacturers announced investments of almost €50 billion in the US.

An Investigate Europe analysis found that more than a third of the 46 planned factories will be built and operated by non-European companies. This includes companies from China, such as CATL. The world’s largest manufacturer of lithium-ion batteries plans to produce cells in Erfurt, Germany, and Debrecen in Hungary, for use in Mercedes sports cars.

But Europe’s plans seem dwarfed by China’s, which dominates the world market. By 2021, Chinese factories produced batteries with a capacity of 655 GWh. That is three-quarters of global production.

And it is uncertain how many of the big announcements will actually come to fruition in the end. "The EU’s production capacity is based on manufacturers’ announcements, which are often withdrawn and are not independently verified,” the European Court of Auditors recently warned.

Especially as the massive US subsidy programme, the Inflation Reduction Act, threatens to poach several battery factory projects from Europe. In the first nine months after the US stimulus package came into effect, car and battery manufacturers announced investments of almost €50 billion in the US.

And it is uncertain whether the EU can do anything to counter this, says Julia Poliscanova, senior director of the NGO Transport & Environment. "Trying to compete with the US or China is like entering a Formula 1 race with a Fiat 500." In a June report, the European Court of Auditors also made a sobering observation: “The EU’s battery value chain remains strongly dependent on supplies from outside the EU. From 2030 onwards, EU manufacturers face a looming shortage of battery raw materials.”

But in their attempt to break away from Chinese dominance, European carmakers could be getting help from an unexpected source: China.

In March this year, Chinese battery manufacturer Hina unveiled the first car powered by sodium-ion batteries. These batteries use sodium ions instead of lithium to move from the cathode to the anode. Hina’s car has a range of 250 kilometres, enough for city driving.

"Few in Germany saw this coming," says Maximilian Fichtner, a battery expert at the University of Ulm. "Some actors simply didn’t have the foresight."

So now it is Chinese companies that are driving the next generation of batteries. At the end of the year, battery giant CATL plans to deliver sodium-ion batteries that could one day power European cars.

Editors: Chris Matthews and Ingeborg Eliassen

Graphics: Marta Portocarrero

This investigation is supported by Journalismfund Europe’s Investigation Grants for Environmental Journalism.

But in their attempt to break away from Chinese dominance, European carmakers could be getting help from an unexpected source: China.

In March this year, Chinese battery manufacturer Hina unveiled the first car powered by sodium-ion batteries. These batteries use sodium ions instead of lithium to move from the cathode to the anode. Hina’s car has a range of 250 kilometres, enough for city driving.

"Few in Germany saw this coming," says Maximilian Fichtner, a battery expert at the University of Ulm. "Some actors simply didn’t have the foresight."

So now it is Chinese companies that are driving the next generation of batteries. At the end of the year, battery giant CATL plans to deliver sodium-ion batteries that could one day power European cars.

Editors: Chris Matthews and Ingeborg Eliassen

Graphics: Marta Portocarrero

This investigation is supported by Journalismfund Europe’s Investigation Grants for Environmental Journalism.