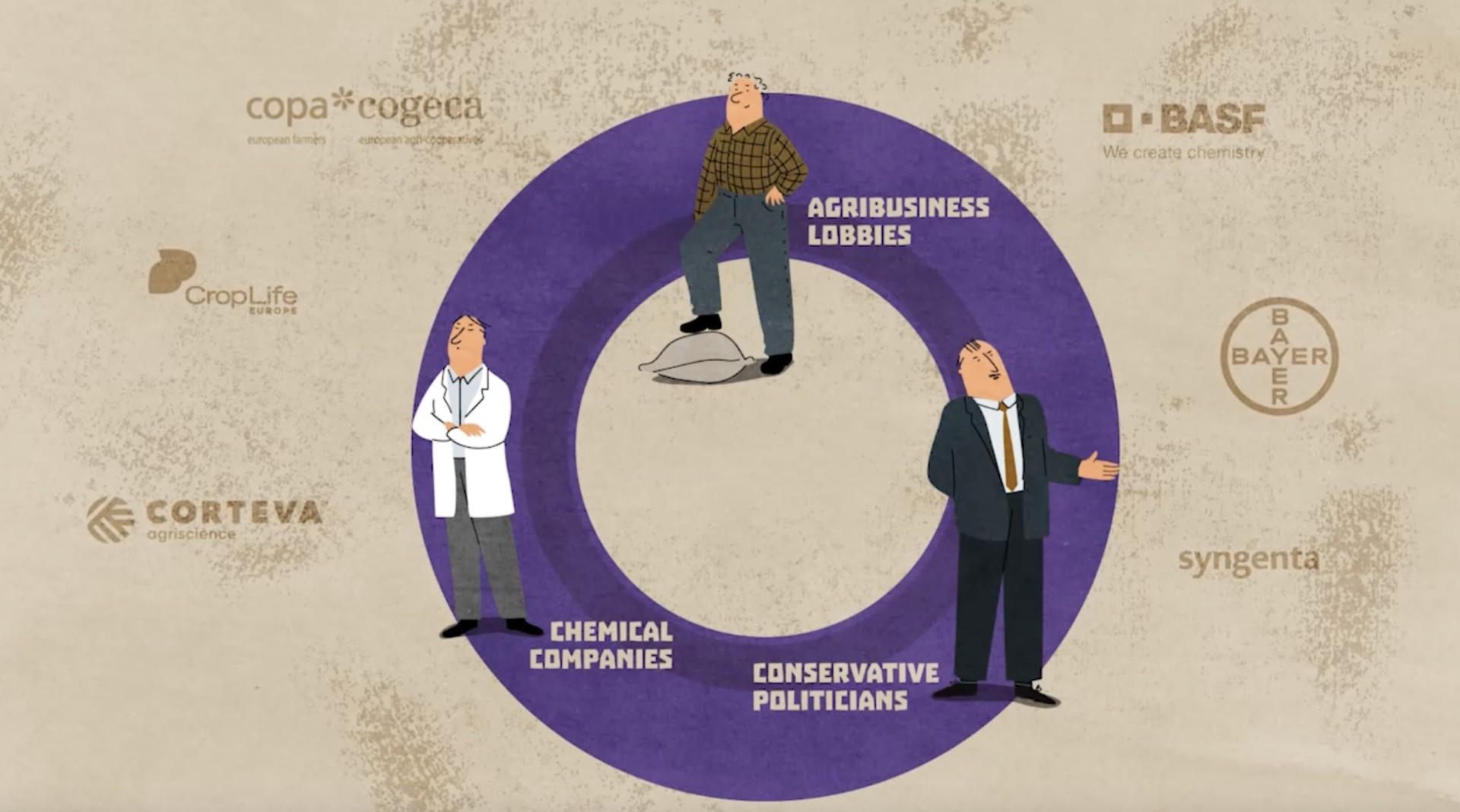

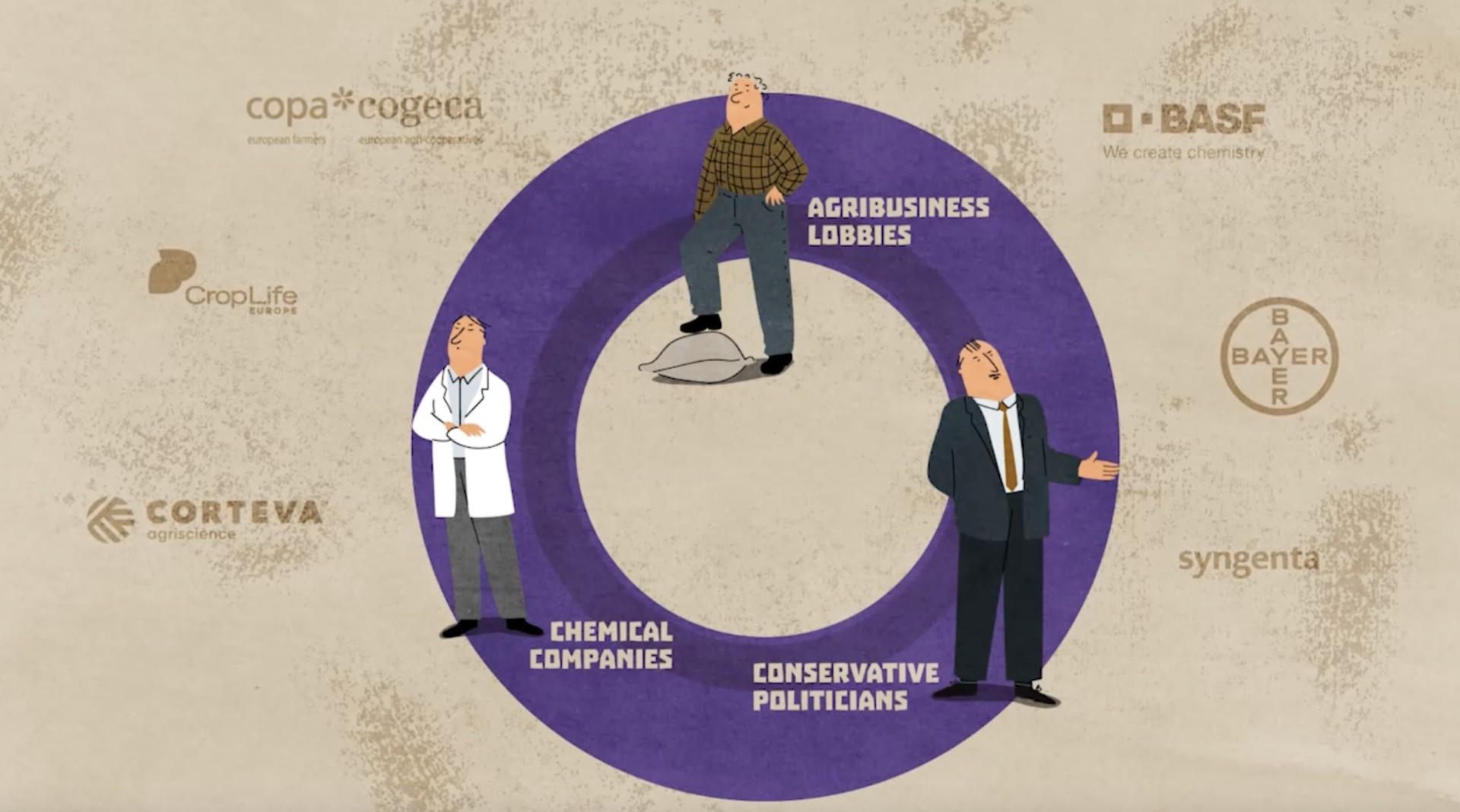

About Silent DeathEurope is stuck in a toxic relationship. For decades, farmers have relied on chemicals to produce the food that feeds the continent. The perils of pesticides are widely known, but their use remains largely unchecked. As a biodiversity crisis unfolds, can Europe address its silent pesticide problem?

Cross-border stories from a changing Europe, in your inbox.

Cross-border stories from a changing Europe, in your inbox.