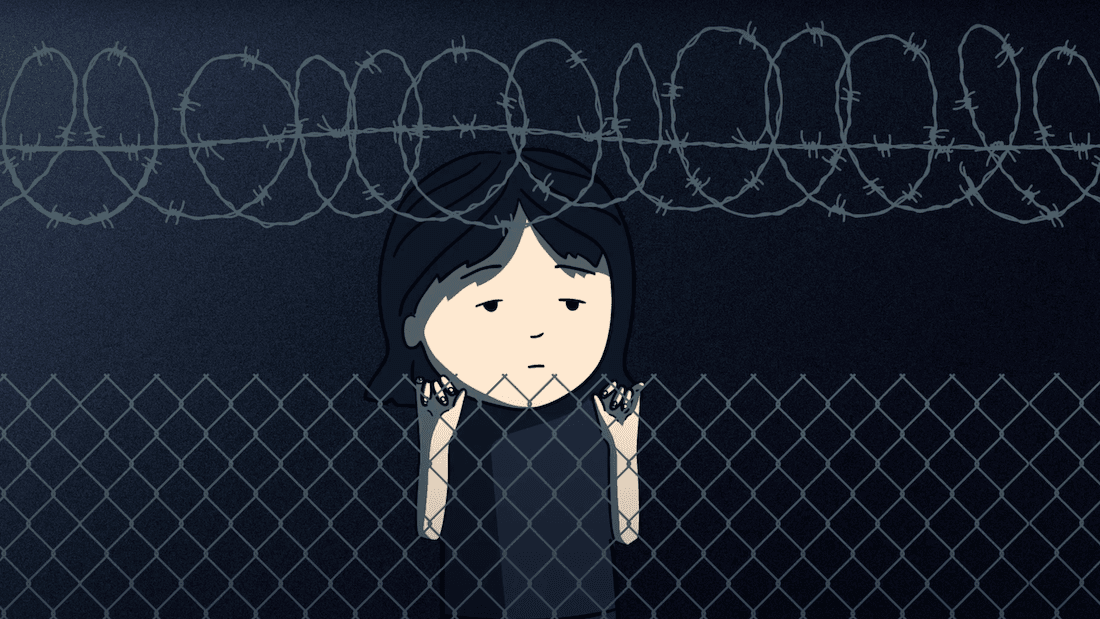

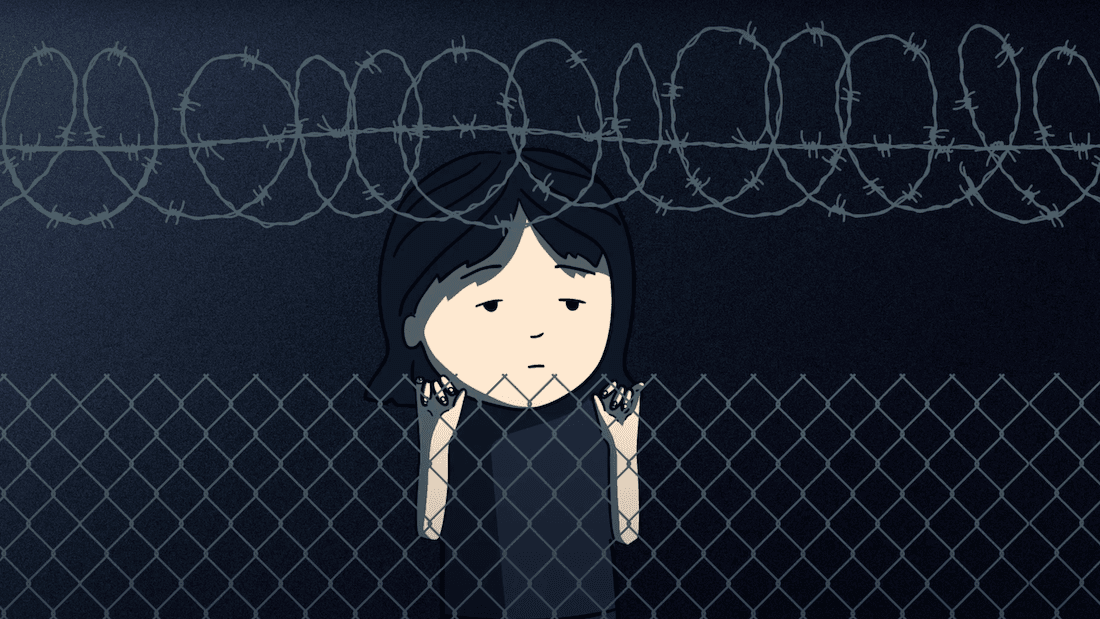

About Minor MigrantsEuropean society has been swift to condemn President Trump’s appalling imprisonment of minor migrants fleeing conflict and poverty in Latin America. But with children making up a third of the refugees and migrants coming to Europe, is Europe’s record really any better?

Cross-border stories from a changing Europe, in your inbox.

Cross-border stories from a changing Europe, in your inbox.