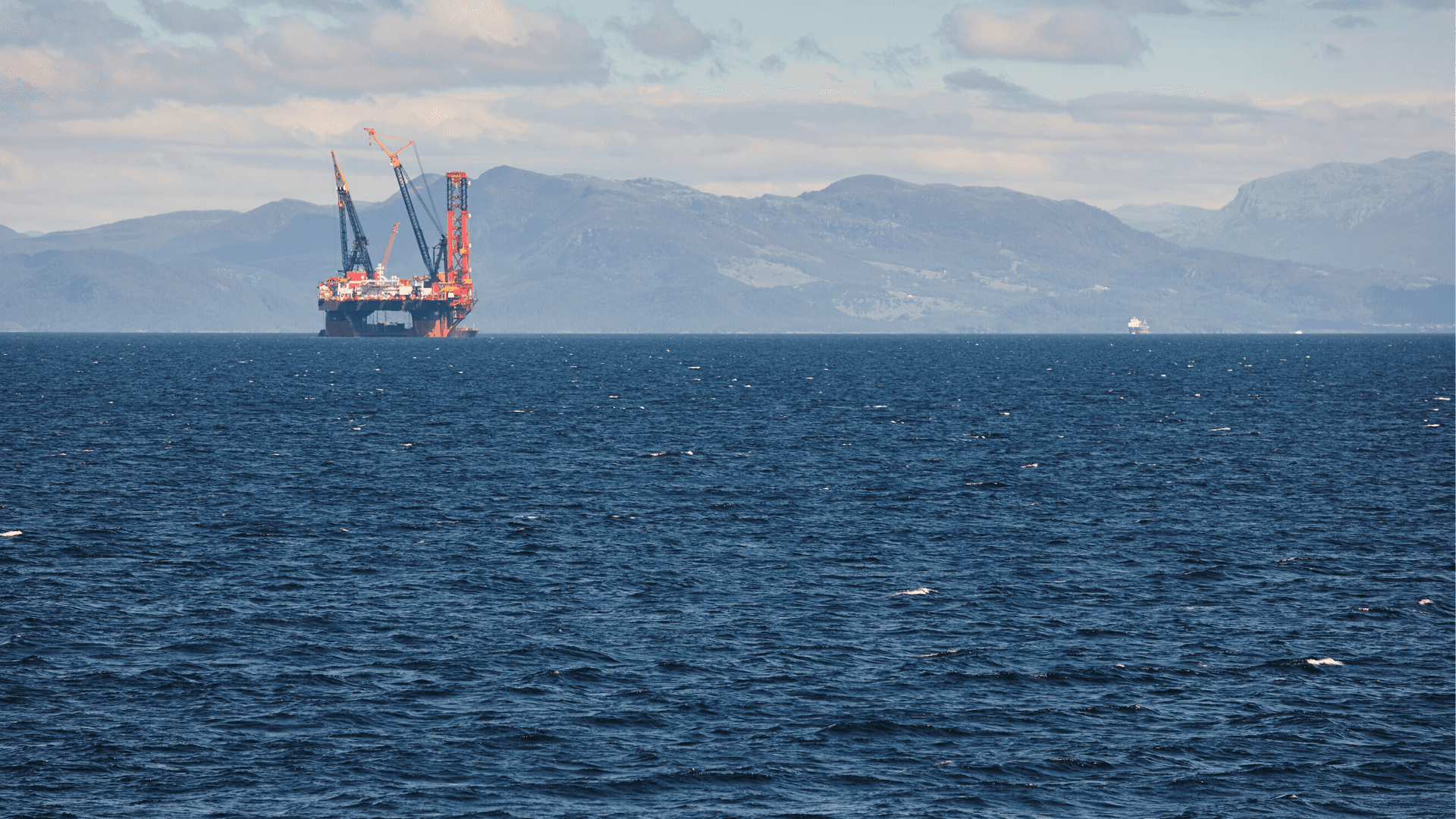

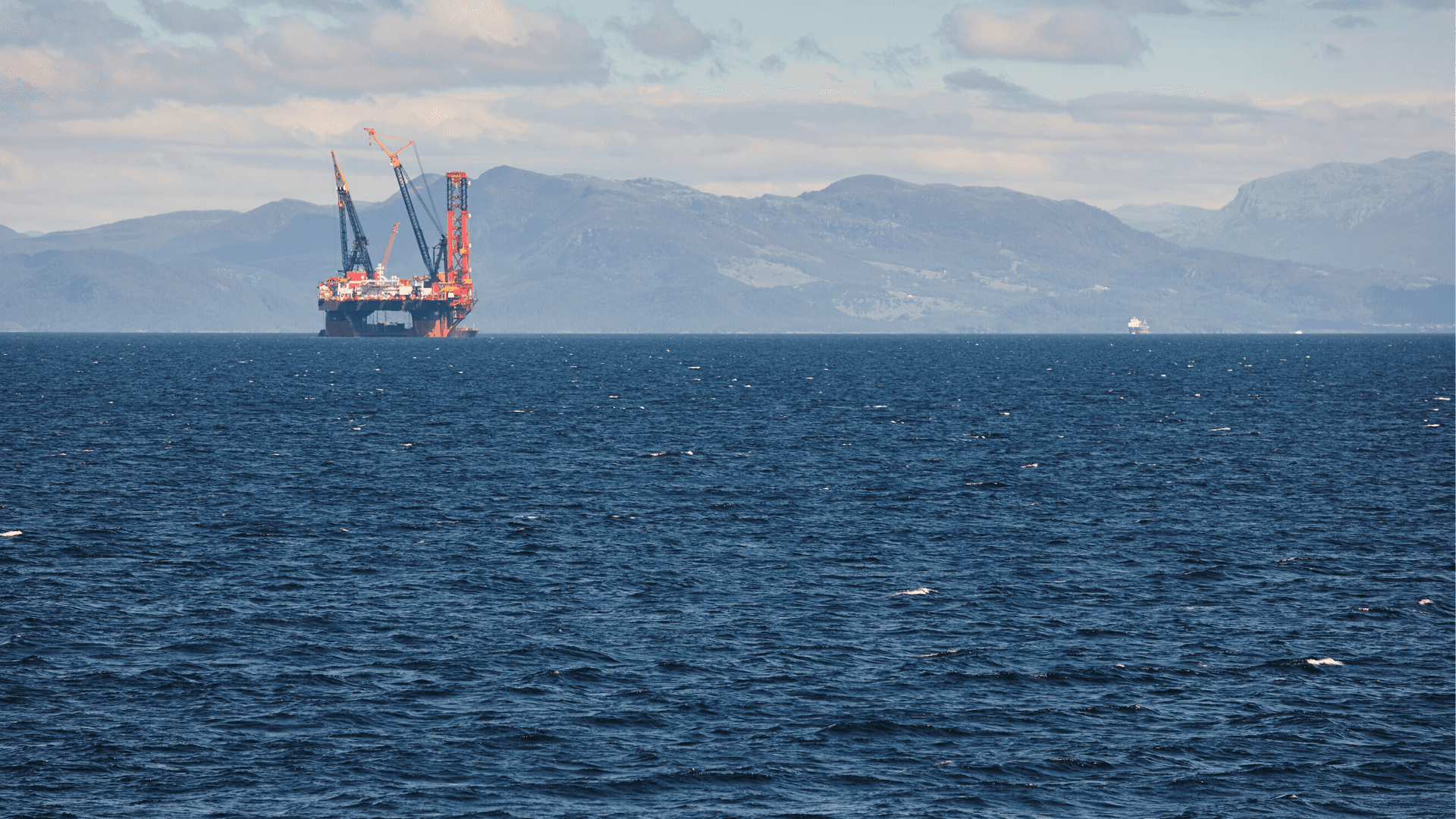

About Dirty subsidies2020 was supposed to be the year the EU would launch its ambitious plan to tackle the climate crisis. But why does Europe sabotage its climate goals by subsidising the fossil sector by more than €137 billion per year?

Cross-border stories from a changing Europe, in your inbox.

Cross-border stories from a changing Europe, in your inbox.